A hidden landscape

Lost designs and new plantations...history unites with today's natural landscape to create something newly natural

Chère amie, cher ami,

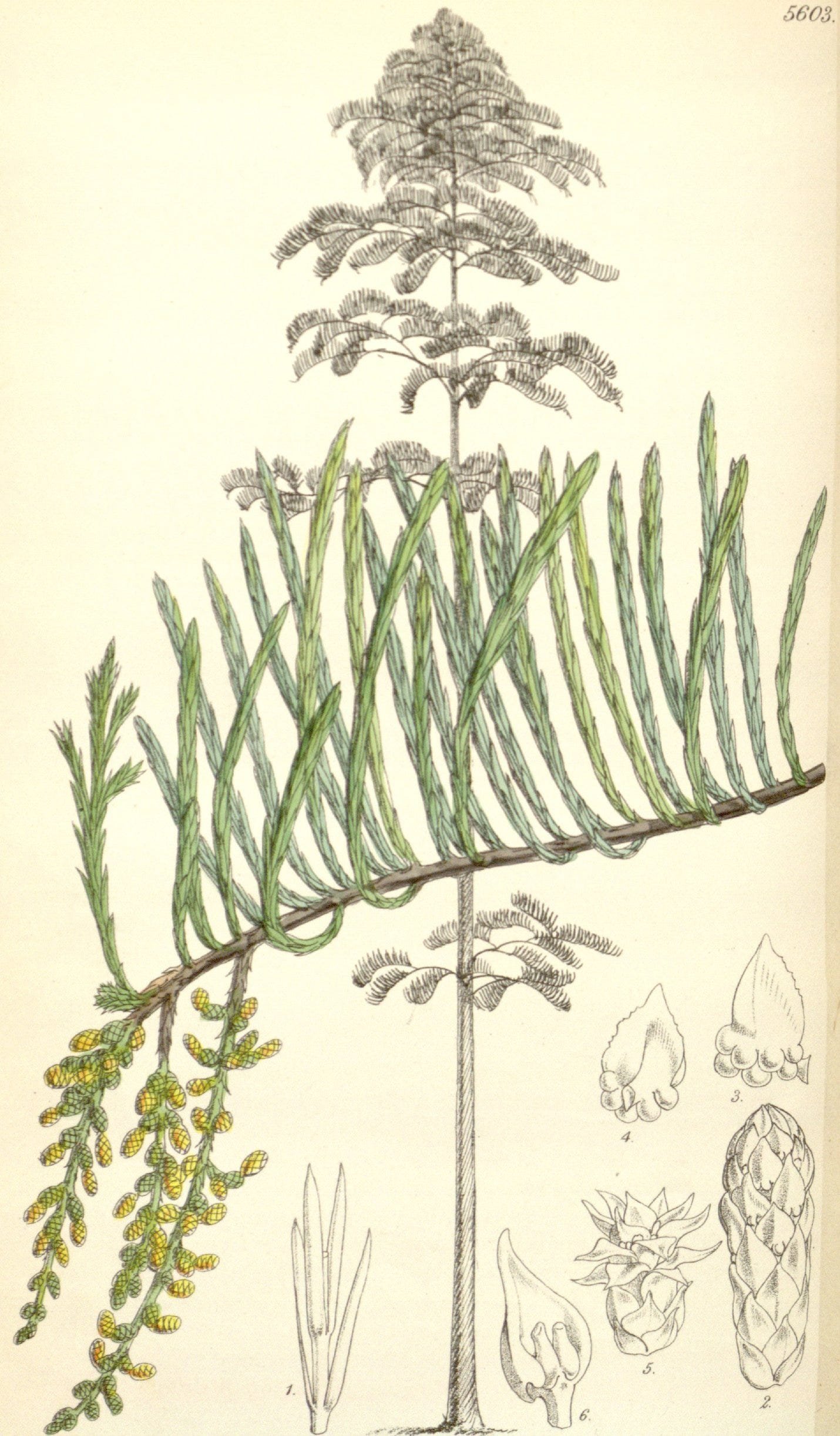

Above: The naturalist and botanical artist Mark Catesby painted this parrot taking a nip of a scale from the cone of a swamp cypress, Taxodium distichum, for the 1754 edition of his "Natural History." In the 1720s, he explored the southern British colonies in the New World. His work was quickly translated into French.

It’s a very warm June day at Chateau de Courtomer.

In the pasture behind the Chateau, the calves are taking a mid-morning rest. Slender legs tucked under their delicate bodies, they doze amid buttercups and the lengthening blades of green grass. Their mothers continue to eat industriously. In these final days of spring, the grass is still tender.

“Et encore riche en protéine et sucre!” Madame Brigitte, our farmer’s wife, informs me.

As grass matures during the summer, its nutritional content falls. That’s why, as soon as we had a few sunny days in the middle of May, our farmer began cutting, raking, tedding, and baling the young grass in the prairies and around the Chateau. The fluffed and dried grass is pressed into les grosses balles, envelopped in plastic, and stocked in our hangar behind the Temple.

It’s a costly process, but the preserved grass is precious during the long winter months. Plus, the cut grass grows back in time to make hay. Enrubannage, as this process is called, is a new technology in the French countryside. It started to take off in the 1990s, but with typical Norman prudence, we waited to make sure it worked before investing in the matériel required.

Looking through the double "allée" of linden trees to the single "rangée" of lindens on the other side of the cour d'entrée...the grass has been cut and now regrows.

The benefits of enrubannage are such that now we make it in every aireavailable. Besides the hayfields, we mow the little paddock beside the graveyard, the old horse pastures next to the stables, the grassy centers of the farmyard and the cour d’entrée. Even the Great Lawn in front of the Chateau offers up its greensward.

“Ah, non!” enunciated Madame Brigitte in a censorious tone. “Pas partout!” She shook her head. A fine gardener herself, her flowers stay in borders around her house. Our plantings have invaded the agricultural domain.

Mowing the parc and its Great Lawn has become a delicate affair for our farmer.

Two years ago, we planted daffodils in swathes across the grass. The leaves must ripen to yellow before they are cut, a process that lasts into June. Otherwise, the bulbs will shrivel up. They won’t make blooms for next spring. And this winter, after much consideration and research, we put in a grove of Taxodium distichum, cyprès de la Louisiane, otherwise known as swamp cypress. It fills a damp clearing between the copse and the big pasture to the east of the Chateau. The trees are still small, easily confused with grass and wildflowers. Unlike the orchard in the farmyard, with its rows of precisely placed pommiers, the Taxodium are arranged in apparent disorder.

“C’est plus naturel, you see” explained Monsieur Martyn to our farmer. In his heavily-accented French, our English gardener took the same occasion to expand about the ripening daffodils.

Monsieur Jean-Yves made no comment. But he suggested that Martyn cut a swathe around the plantation before he started mowing.

While our farmers work les terres du château with a proper dedication to improved techniques and agrarian productivity, Monsieur Martyn and I are engaged on another mission. Our gardener, true to his English origins, sees potential mixed borders in every corner of the grounds and flowering vines on every stone wall.

I seek the hidden landscape. In overgrown plantings, in old stumps, in the vestiges of garden walls, the estate’s lost design begins to emerge.

Looking across the the Great Lawn, part of which will soon be cut for hay. The grouping of trees is made up of mature volunteers and an allée originally planted in horse chestnuts.

Part of the archives of the Courtomer family are still preserved in the Chateau. In among wedding contracts and deeds, I found an 18th-century sketch of the grounds and a 17th-century description of trees. On the lawn is a huge sequoia, about 120 years old, survivor of tempests and droughts; there are tall, broad-girthed oaks and plane trees planted centuries ago. And we may have found a garden folly...or perhaps a ruined tower...in the far corner of the home pasture. In old photographs, we can see that this part of the estate was once part of the park. A cluster of Western Red Cedar where the cows like to scratch their backs and refresh themselves in the shade is all that remains.

Of course, I wouldn’t like to suggest to our farmers that the cows should be evicted from the pasture. Landscape evolves, like the Chateau itself, and like the families that followed the Norman seigneur who first took possession here and made it his fief.

I’m looking for a new way to interpret the espace vert that surrounds us.

Streams that cut through the meadows and the parc, the shadows cast by solitary trees on the grass, a slope that falls away to a little swamp, the grove of trees filtering light on stone and wildflowers... this landscape, natural and man-made, tempered by the passage of time, invites new expression. Within the distinctive paysage around the Chateau, new gardens and revived historical plantings must find their place.

Before this new vision des choses occurred to me, I struggled to impose a forme classique on the Chateau. The edges of the Great Lawn, overgrown with brambles and saplings, wobbled indistinctly to a pair of iron gates set off to one side. There was no grande perspective that led the eye from the front door of the Chateau to a focal point at the end of the parc. At the center of the would-be vista, someone had actually installed a telephone pole.

Louis XIV would have insisted on a fountain or at least an obelisk.

But in the days of Louis XIV, of course, the heyday of the Chateau was long past. The family had been unfortunate in war and choice of religion. It had relinquished its Protestant faith only at the last moment, under threat of exile and imprisonment. Two generations of men had been wiped out in military service. Their widows and children, living on restricted means in a tumbling-down medieval château, never thought of hiring a gardener like André Le Nôtre, designer of the parterres, fountains, and bosquets of Versailles.

Courtomer began its comeback a century later. In France, this was the age of the great botanists and the jardin naturel.

At Versailles, Louis XIV’s gardeners had used native oaks, lindens, and chestnuts, massed for effect in bosquets and allées. These were dug up from the surrounding countryside, including Normandy, and transported to the palace grounds. Louis XIV’s équipe discovered how to transplant these large trees. They learned how to grow specimens from seed and cuttings. By the 1750s, the plant nursery of Versailles produced hundreds of thousands of trees each year.

Snapshot of our sequoia on a sunny June morning. This tree is a lone survivor of several sequoia planted in Courtomer's "parc" in the 1850s.

Louis’s heir, coming of age in the mid-18th century, used the body of knowledge acquired at Versailles to develop the richest botanical garden in Europe. Under his patronage, men who were scientifiques as well as plantsmen were appointed to run the Jardin du Roi in Paris and Louis XV’s own Trianon garden in Versailles.

The king founded botanical gardens at France’s international ports. Here, les végétaux that had been transported over the waves could be tended, studied, and reproduced. Ship’s captains were required to bring back seeds and plants from their voyages. Near Courtomer, the king founded botanical gardens at Rouen, Caen, and Cherbourg. You can still visit them today.

This was the age of the private arboretum, too. As the plant collector François-André Michaux ironically observed half a century later, if one wanted to know how American species survived in France, one had only to visit the gardens of “grand seigneurs.” Most of the plants he and his father sent back from their voyages for the king were diverted “à des particuliers, qui en garnissoient leurs maisons de campagne.” Instead of being used for science, plant specimens ornamented country estates.

Perhaps that is what happened at our own Chateau de Courtomer! During the last quarter of the 18th century, the Marquis and his family re-established their fortunes. They began a vast program of building and improvements. On the eve of the Revolution in 1789, they had just finished reconstructing the Chateau on its medieval foundations.

It is delightful to imagine that at 18th-century Courtomer, American maples and magnolias took root; or that there was a scion of the famous Sophora du Japon, imported as a seed from China in 1753 and still thriving at the Trianon, planted in our parc.

That a Taxodium distichum was tucked into the earth with the same loving care as Martyn has given our own little grove of Louisiana cypress.

That in the library were well-thumbed copies of Michaux’s Histoire des chênes de l'Amérique of 1801, about American oaks. And on the desk, enthusiastic letters from members of the Académie royale in the nearby city of Rouen, whose founding members met in a botanical garden and welcomed such illustrious speakers as the comte de Buffon, naturalist and head of the Jardin du Roi.

The English plantsman John Tradescant the Younger was the first European to describe the swamp cypress, whilst on a plant-collecting expedition in North America in 1637. He brought a specimen to England, where it flourished. France began its botanical explorations later; the earliest French specimens date from French exploration of the flora of Louisiana, in the 18th century. Illustration is from a herbarium at Oxford University.

In upcoming months, we’ll be designing our planting program at Courtomer. To bring new plantations in harmony with the natural landscape and with the moats, stone walls, ruined folly, and other man-made elements demands attention. But to be inspired by the plant-collectors of yore promises many delightful hours in archives and libraries. There will be day trips to visit botanical gardens! And long walks around the Chateau grounds with a pencil and drawing pad.

Monsieur Martyn is already making lists.

Interrupting these pleasant reveries, a gentle hum deepened into the throb of a tractor engine. The grass is being cut on the Great Lawn. As we imagine our 21st-century arboretum, we recall that a farmer’s work and a herd of cows also shape the landscape of Courtomer.

Et tant mieux!

Here's to summer sunshine,

Elizabeth