The noble pigeon

Feathered pet...fleeting shadow of the Ancien Regime...and "pigeon de combat" in June days almost forgotten...

Sunday, June 5, 2022

Above: the Protestant Temple at Chateau de Courtomer as a dovecot or "pigeonnier"

Chère amie, cher ami,

Shortly after daybreak, the dove’s yearning cry carries across the pastures and the Great Lawn at Courtomer. Its long, soft call reverberates and falls, a gentle lament in the pale, cool air. It’s as if the coursing sap and intense sunlight of spring are melancholy reminders that just as the seasons ineluctably shift, there is no respite from the passage of time.

Spring pushes forward, lengthening the days, unfurling leaves, thrusting buds out of bare stems, pulling open the petals of early flowering dogwoods and magnolias. From tentative beginnings in cold March, spring greets May with bold assurance. And now, in June, we are only three weeks from the summer solstice.

When our Edward was about 10 years old, the vacher François brought over a white pigeon. It had blundered into the basse-cour from parts unknown. Our cowherd suggested le petit would like it as a pet.

François and his wife Luisette kept pigeons, the way they kept rabbits and a pig. In time, all the inhabitants of the little cour beside their house passed from this life into the pantry, in the form of fricassée, terrines, saucissons and other tasty morsels. But this pigeon didn’t belong to them…and perhaps they thought it was ill-luck to bake a white pigeon – so evocative of the Saint Esprit – into a pie.

Feathered pets: "Innocence tenant deux pigeons"..."Innocence holds two doves" by the 18th-century French painter J-B Greuze was used as a postage stamp in 1954 to raise money for the Red Cross.

Like all pigeons, as we learned, Edward’s pigeon had its own mind. He would flutter away from his young master, ignoring a morning feed of oats to perch in a linden tree. Edward, encouraged by his younger cousin Catherine, would jab and jostle Cher Ami Blanc off his branch with a long pole. Docile, the pigeon would allow itself to be carried back to its pen. But Blanc did not stay with us long. Rested and well-fed, one day he found the strength to follow his instinct and fly home, back to his own colombier.

“How did he find his home?” Edward wondered.

The pigeon, his older brother kindly explained, has a homing instinct. It makes a mental map of the earth’s magnetic field to orient itself as it leaves its nest and flies away. Also, its sense of smell guides it homeward. Probably it uses its vision, too, added Edward, who had been observing Blanc’s bright round eyes.

“And pigeons mate for life,” I told him and added, to console him, “Probably Cher Ami Blanc has a chère amie calling him home.”

“Chastity is especially observed by it, and promiscuous intercourse is a thing quite unknown,” quoted Monsieur.

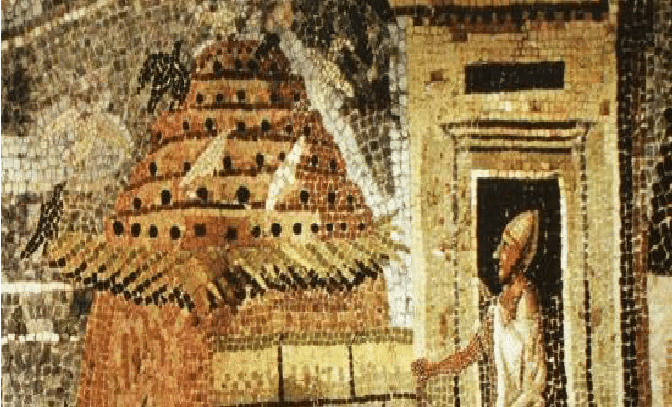

A mosaic from the 1st Century B.C. shows what would have seemed an exotic dovecot in Northern Africa to the Romans. The entire mosaic, in the temple of Fortuna Primogenia outside Rome, displays the Nile winding from Ethiopia to the Mediterranean Sea.

My husband was leafing through the “pigeon” chapter in a copy of Pliny the Elder’s “Natural History,” written in 77 A.D. The Romans had adopted pigeon-keeping from the Greeks, who in turn were said to have taken them from captured Persian ships. Cyrus the Great, emperor of Persia, used pigeons to carry messages to his naval commanders in the 7th century B.C.

The pigeon had aroused wide-ranging interests in our family.

Pigeons, descended from the wild rock dove, were first domesticated – like cattle, sheep and goats – thousands of years ago in the Fertile Crescent. Henry, studying Latin at school, told us that the Romans called doves “columbae” from the “columina,” the gables of a house where the birds liked to nest. The Greeks and Romans recognized a distinction between a shy wild dove, a larger, tamer dove and a third variety, thought to be a cross between the two. The latter was called in Greek, peristeri.

With their characteristic enthusiasm for both luxury and practical improvements, the Romans took to pigeon-raising. No Roman country villa was complete without a “columbarium.” In Rome itself, pigeons were kept on rooftops. Agricultural treatises gave detailed instructions on how to raise them. A "columbarium" was for a small flock of doves; the “peristeron” could house 5,000 birds.

As from time immemorial, pigeons were fattened for the table and tamed as pets. And all the Roman authors pointed to the value of guano for fertilizing fields.

Like indoor plumbing and wine, pigeons came to France with the Roman conquerors and were adopted with gusto. By the time Rome’s rule came to an end 500 years later -- and although indoor plumbing fell into disuse -- dovecots were to be found throughout France. The French invented the use of the “potence,” a ladder that swivels around a central axis and allows the pigeon-keeper to reach the nests for cleaning and gathering eggs or young pigeons.

Early photograph of a terracotta pigeon found at a French site from Gallo-Roman times. Statuettes of doves, associated with playfulness and innocence, were often given to children as toys or buried with them in tombs.

But pigeon-raising has its disadvantages, as the French also learned. Guano, called “colombine” in French, is useful only to farmers and their crops. It’s still illegal to allow pigeons to lay eggs on your windowsills in Paris.

And unless pigeons are fed by their owner, they will feast on available fodder in someone else’s property. Raising large quantities of pigeons in a “columbier” became a privilege accorded only to those with the means to maintain them.

“Que ceux colombs se puissent pourvoir sur luy ou sur ses hommes,” admonishes an “ancien coutume,” or customary law. “That these doves be maintained by the owner or his men.”

A particularly handsome "colombier" from the early 1500s can be seen at Varengeville near Dieppe. The projecting row of stones discourages vermin from climbing into the "boulins," the holes where the birds enter and depart.

Nevertheless, the “colombs” were a perpetual source of discontent and legal squabbles in the countryside. There were quarrels about whether a dovecot was a full-scale “colombier” or just a “volière,” a wooden cage for a few domesticated birds.

The laws governing the colombier grew increasingly strict. In theory, no new dovecots could be built. Their owner must possess sufficient land to feed the pigeons, and the land had to be in one large contiguous parcel so the pigeons could not eat at someone else’s expense. In Normandy, the right to own a colombier was attached to the “fief de haubert,” the amount of land required to support one mounted knight. And in case of a division of Norman property, no matter how large, only one heir could keep the existing dovecot.

A sketch made before the medieval Chateau de Courtomer was pulled down and rebuilt in the 18th century shows the location of the old colombier in the basse-cour. It vanished, like the coat of arms over the Chateau’s entrance, during the French Revolution. The “droit de colombier,” with other noble rights and marks of distinction, was abolished in 1789.

“But there is a pigeonnier at Courtomer!” remonstrated Viola, as we remembered le petit's pigeon.

Henry shook his head.

“That’s just camouflage,” he said. “It's a Protestant Temple.”

Just as the family at Courtomer gave up their colombier and their coat of arms during the Revolution in 1789, their forebears had given up their religion and their Temple after the Revocation of the Edit de Nantes a century earlier.

What looks like a pigeonnier, with its tall, steep roof and line of niches in the façade, was actually built as a place of worship in the 17th century.

Like many Norman aristocrats, the Courtomer family had converted to la Réforme in the 1500s. After the end of religious toleration in 1682 and under threat of prison, confiscation and exile, they had abjured their “Reformée” faith. Unlike most Protestant temples in France, however, Courtomer’s was spared – for inside it are buried three generations of seigneurs, with their wives and daughters, who had loyally served the kings of France.

The Temple as a bull pen at Chateau de Courtomer in 2003. Earlier, it had also been a stable and a dairy.

Nevertheless, the family was under suspicion, and in response to an accusation alleging illicit services were being held in the old Temple, they stated that it was now a dairy. The agricultural destiny of the building continued until it was used to stable four of the Comte de Pelet’s stallions and then a few bulls. And at some point, a series of niches for doves was opened in the brick façade facing the Chateau. Pigeons were still a delicacy, after all!

“But Cher Ami!” protested Edward. “No-one would eat him!”

When François presented le petit with the dove, we knocked the dust off the spine of an old children’s book we had never read, “Cher Ami: The Story of a Carrier Pigeon.”

“Dear Friend” was no mere carrier pigeon. He was a heroic pigeon de combat. Except that he was grey with an iridescent purple neck, Cher Ami was a fine namesake for Blanc.

Following the ancient tradition of colombophilie militaire, Cher Ami was just six months old when he flew his last mission over enemy lines in the Grande Guerre.

Machine-gunners hit him in the breast and cost him an eye and a foot. He fell out of the sky, then managed to climb back in the air. And he carried a message that rescued the tattered remnants of the American 77th Battalion, trapped in the Argonne Forest northwest of Verdun. This was the last offensive of the war, “les Cent Jours” that ended with the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

The “Lost” Battalion had started out as 550 American soldiers encircled by the German Army and beyond radio-signaling range for rescue. They were caught in deadly American “friendly fire.” Runners and the other pigeons were dead. Cher Ami was launched with a message that ended “our artillery is dropping directly on us. For Heaven’s sake, stop it.” Rescued the next day, 194 men survived.

Cher Ami was awarded the Croix de Guerre. His trainer fashioned a new foot from wood. And Pershing himself, General of the American Armies, saw Cher Ami safely onto the ship that took him to his final home in New Jersey.

Cher Ami never made a full recovery. He died a year later and was stuffed.

“That’s horrible!” exclaimed Catherine.

“No, ma cousine,” Henry gently rebuked her. “It’s a great honor. Remember Le Vizir?”

We had taken the children to the Musée des Armées in Paris. Le Vizir was Napoleon’s last horse. He has recently been restuffed and is again on display. Cher Ami, meanwhile, is in the “Price of Freedom” exhibit at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

“The Egyptians stuffed, or rather mummified ibises and vultures,” added Catherine, thoughtfully. “And pigeons.”

Another brave "pigeon de Verdun," Vaillant was also preserved for posterity. On June 4, 1916, Vaillant flew through poisonous gas from the Fort de Vaux in the midst of bombardments. Like Cher Ami, he carried a message from his stranded battalion; the final line reads "This is my last pigeon."

Cher Ami, of course, was not the only heroic military pigeons France has known. The French first used pigeons to carry military messages in the Franco-Prussian conflict of 1870, during the siege of Paris. And in the Second World War, the famous Gustav flew 150 miles in a little over four hours to carry news of the Normandy landings to England on June 6, 1944.

Like Cher Ami, he was decorated for bravery.

The pigeon, gentle, faithful, and eh oui! delicious is now found only rarely in the basse-cours of Normandy. The few colombiers that survived the Revolution are Monuments historiques.

The "pigeon de combat," hero of those unforgettable and almost forgotten days, has gone the way of Napoleon's cavalry horse.

But from the trees in our park on these lengthening spring evenings, the colombe's tremulous call still sounds, soft and melancholy. We remember a fleeting feathered pet, the long-gone families of Courtomer, and man’s willing comrade in arms on other days in early June.

A bientôt au Chateau,

Elisabeth

P.S. You might enjoy Gustav being decorated, a British news clip of 1944.

As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday or special gathering at the Farmhouse or the Chateau. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.