Shooting star, a shower of stones

Meteorites rain down near the Chateau...and a famous meteor shower 220 years ago in a local town takes us back to the creation of the universe...

Above: shooting stars a couple of years ago in La Perrière, not far from Courtomer

Monday, June 13, 2022

Chère amie, cher ami,

“Voyez, l’orge y était déjà bien montée!” said our neighbor Rolland. “Elle n’est pas tombée au bon moment, votre météorite!”

He leaned on his stick, his felt hat pulled down against the bright June sun, the lines around his light blue eyes crinkling the delicate skin of his temples.

“That’s what I told them,” he continued. “Look, the oats are already up. Your meteorite has not chosen the right moment to fall in my field!”

On April 16, a shooting star exploded in the night skies above the little cathedral town of Sées, about nine miles from the Chateau. Flung through the air at 125 miles an hour, the particles landed in fields and farmyards nearby. By the time they touched ground, the meteorites were as polished as pebbles that had been sanded in the ocean for decades.

The whole event, from the time the “étoile filante” appeared near the moon to its silent explosion in the icy realms of the upper atmosphere, lasted about ten seconds.

A week later, two astronomers from Paris drove out to the Orne in great excitement. They went from farm to farm, asking for permission to scour the fields for meteorites. The meteor itself, they explained, was a chunk of rock from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Planetologist Sylvain Bouley of the Société astronomique de France, and Nicolas Colas, astronomer at the Observatoire de Paris, came out to study the recent meteorite shower near our local cathedral town of Sées.

“Of course it shattered,” Rolland observed. “They said it was going 45,000 kilometers an hour when it hit our atmosphere.”

Asteroids are thought to be made of matter formed before the existence of the planets. The biggest one seen in the belt is 389 miles across. But most asteroids are quite small.

Since this meteor had lasted twice as long in the Earth’s atmosphere as the usual shooting star, some of the pieces would be quite large. Perhaps, the astronomers predicted, the size of an orange!

“Did you see that movie “Don’t Look Up”?” Rolland asked us.

“Pfff! I told them to come back after I harvest my oats.”

As long as we have known him, Rolland’s intellectual and artistic universe has been bounded by the Age Classique, that which preceded the Age des Lumières, the French Enlightenment. This doomed latter period, according to him, was the beginning of the Revolution and successive modern and contemporary ills.

So we were surprised to learn that he had been watching “le Netflix.”

This isn’t the first time that meteorites have fallen in the département of the Orne, of course. Shooting stars, or meteors, deposit about 48 tons of space rock on the Earth every year. But the Orne, and in particular an area about 28 miles northwest of Courtomer, is famous in the field of meteoritics. In fact, the study of meteorites as a branch of science began with events in L’Aigle.

The 1803 meteor explosion over this busy market town was one of those transformative moments when mainstream ideas suddenly shift and open the way to new understandings. It led to current theories that explain how our solar system was created.

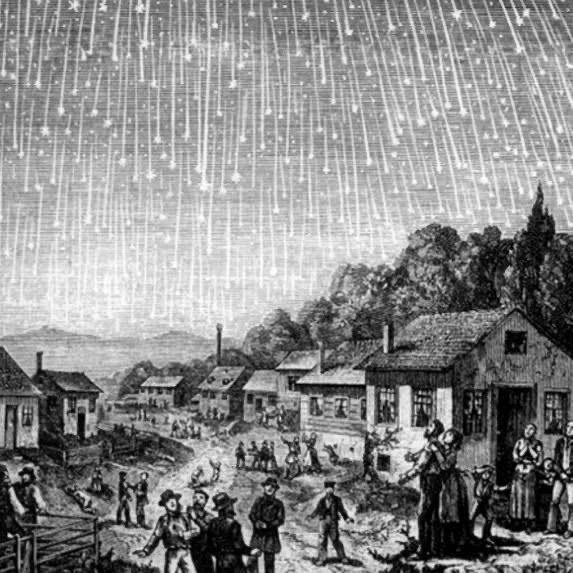

The meteorite shower in L'Aigle, about 220 years ago, in a contemporary engraving of the remarkable event.

On April 26 in 1803, on a clear and sunny day, the citizens of L’Aigle were stunned – some perhaps literally – by a cascade of stones hurtling down from the sky. First there had been the sound of rolling thunder, a tremendous “fracas” in the heavens. But instead of rain, stones plummeted earthward.

At the time, the origin of meteorites was a divisive topic.

Impossible that stones could fall from the sky! These were the imaginings of foolish paysans, mere superstition.

Still, even the ancients had spoken of them. A meteorite the size of a “wagonload” fell at Aegospotami in 467/6 B.C., the same year as the first historical sighting of Halley’s Comet. It was said to portend the defeat of the Greeks in the Peloponnesian War.

A century later, the Greek philosopher Aristotle dealt with airborne stones in his “Meteorologica,” declaring them the result of a “hot, dry exhalation” from the earth which caught on fire, like lightning, in the clouds. His theoretical framework for understanding the mysteries of nature as interactions of four basic elements (air, water, earth and fire) held sway for centuries.

Meanwhile, the idea that stones falling from the sky augured storms, plagues, crop failures and military defeats also held sway. In the town of Ensisheim in Alsace you can still see a 300-pound meteorite that fell in 1492. It was said to foretell the defeat of French forces at the hands of the Holy Roman Emperor the same year. And for three centuries, it was kept chained inside the town’s church so that it would not “wander.”

By 1803, this way of thinking was outmoded. Scientists now sought explanations that could be proven by experiment or observation. And the great Sir Isaac Newton himself had definitively declared that outer space was empty. Newton came to this conclusion in 1718, based on gravitational calculations.

Yet the respectable and educated citizens of L’Aigle, a substantial market and manufacturing town, had collected more than 3,000 stones that had fallen from the heavens. And many of these witnesses had taken the trouble to make sworn and notarized statements.

A week later, a team of scientifiques led by the mathematician Jean-Baptiste Biot arrived from Paris to study the phenomenon. This was the world’s first scientific expedition to methodically collect and study meteorites.

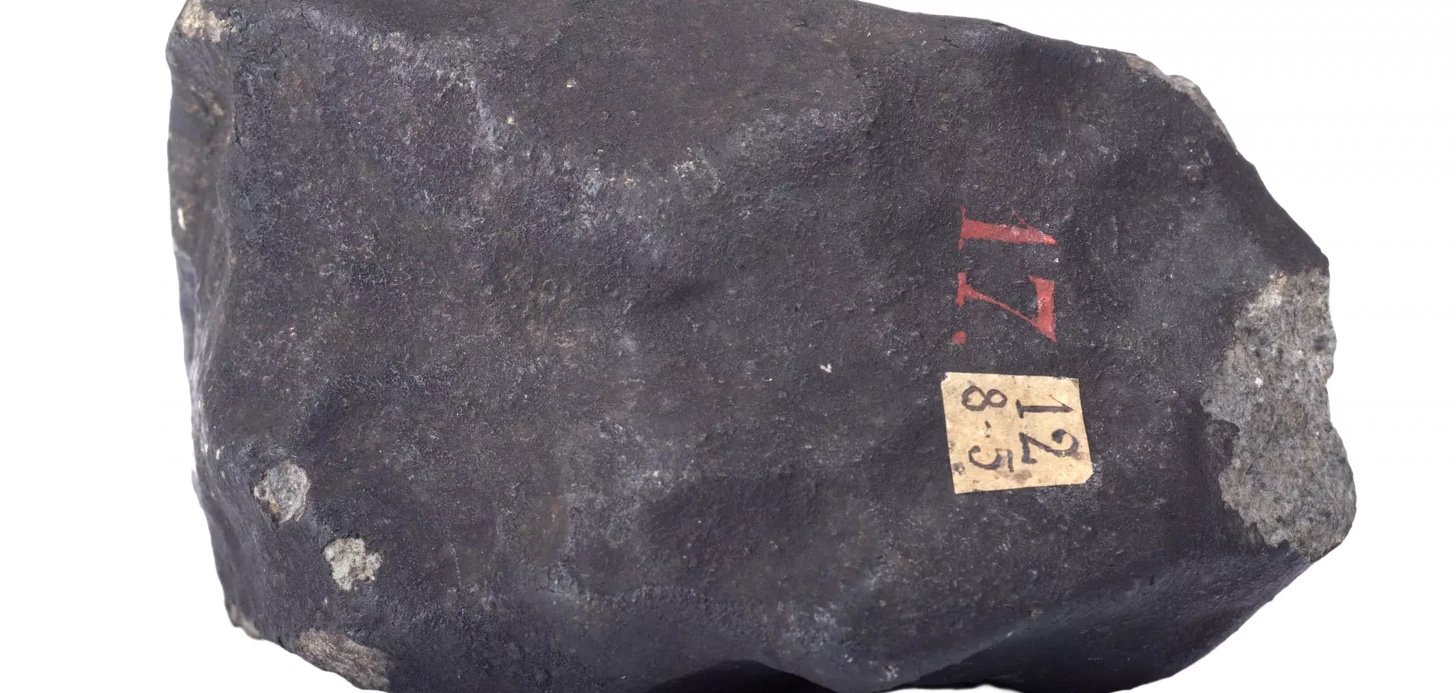

A piece of the asteroid that exploded over L'Aigle in 1803, showering the town with thousands of meteorites. As you can see, very similar to our recently fallen meteorite below. From the Muséum d'Histoire naturelle in Paris.

Mainstream thinking posited that meteorites, since it was impossible that they were made in the sky or came from outer space, had been spewn out by volcanoes. This also explained the shiny, vitrified surface of the stones, which had obviously been subjected to high heat.

Or, as Aristotle himself had speculated about the Aegospotami meteorite, they might have been swept up from the ground by hurricanes and dropped back down.

And if one insisted that the stones came from beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, volcanic eruptions on the Moon might explain them. In fact, however, there was no sign of volcanic activity on the Moon.

The events at L’Aigle in 1803 provided definitive evidence that the falling stones were extraterrestrial. There were no local volcanoes to send them flying, nor had the stones been caught up in a great wind.

Instead, the stones from L’Aigle were identical in texture and composition to stones that had been gathered after similar celestial events over hundreds of years in many parts of the world. Meteorites shared a common origin — and it wasn’t terrestrial.

Today, astronomers believe that meteorites are made of matter that predates even the Sun. There are meteorites that appear to have been shorn off the planet Mars. Meteorites help to understand how our world came into being.

“Voyez!” exclaimed Rolland. “After the astronomers left, I happened to be out checking the young oats.”

He reached into the pocket of his baggy tweed jacket and drew out a dark, polished stone.

“I hope it’s a good omen.”

A bientôt au Chateau,

Elisabeth

One of the meteorites collected near Sées by the astronomer Nicolas Colas.

As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday or special gathering at the Chateau de Courtomer or its Farmhouse. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.