Rabbits in the Basse-cour

...and Madame Francine regrets Clyde, the rebellious white rabbit...

Illustration, Jean Emile Laboureur (1877-1943)

Chère amie, cher ami,

Our trip to the Calchaquí Valley of Northwest Argentina has come to an end…and Courtomer beckons.

It’s a glorious spring day. The light green leaves of the oaks have unfurled; the purple and red leaves of the beech are transparent against the spring sky. The ducks are swimming in the moat, Madame Francine’s hens are scratching for worms in the basse-cour, and her new rabbits are enjoying the vividly named pissenlit and, as Madame Francine calls it, langue de belle-mère – dandelions and nettles (the stinging “tongue of the mother-in-law”), plus stale baguettes.

The rabbits are a new arrival. Three came down from her native country of Pas-de-Calais in the north. Cédric, her son, brought them back from a visit to his sister there.

“De la race! Papillon et Fauve de Bourgogne,” Madame Francine told me proudly, commenting on their fine breeding. Papillon, which means butterfly, is a large-sized breed of rabbit whose sparkling white fur is marked by blotches of crisp black. The purest of the breed will have a butterfly-shaped marking on his nose. Fauve de Bourgogne is a daintier animal, with pelage of a soft reddish gold color called “fauve.”

The provenance of the other two rabbits is less clear. They appeared one day, also with Cédric, along with four more clapiers, or rabbit hutches.

“Mais ils sont un peu près de la même,” she assured me, happily. “They’re about the same.”

Chickens are very well, she remarked. But rabbits also eat many leftovers. And if they don’t lay eggs, they have other uses. She smiled and gave a gentle wink.

“Wait until they get bigger,” she told me.

Intimately linked to the traditional life of the basse-cour, the lapin shares a long history with la civilisation in France. To begin with, it is the only farm animal that originated in Europe.

Sheep, goats and cattle were first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East. They migrated to Europe with the earliest farmers and herdsmen many thousands of years ago, during the Neolithic Age. Chickens, meanwhile, were bred from the wild jungle fowl of Southeast Asia. Phoenician traders introduced them to Europe 10,000 years ago.

But rabbits are native to Southern Europe. Some philologists argue that the word “Spain” comes from Phoenician words meaning “land of the rabbit” or “I-Shpania.” The Romans, invading the Iberian peninsula and ever alert to technical and lifestyle improvements, took up rabbit-raising or “cuniculture.” Rabbits from Spain were shipped throughout the Roman Empire.

Unlike running hot and cold water, paved roads, public toilets, and aqueducts, cuniculture survived the fall of Rome. It was in the east of France, in monasteries, that the practice developed of raising rabbits in artificial warrens made of stone or in “parcs” enclosed by a wide moat. These precautions kept the rabbits from digging to freedom. Traces of medieval “garennes” have also been found in Normandy, not far from Chateau de Courtomer.

Diagram of a man-made stone "garenne," or rabbit warren, from Le Thoureil in the Loire Valley, where the first Benedictine abbey. Saint-Maur-sur-Loire, was established in the mid-6th century.

At first, archeologists interpreted stone "garennes" like the one above as pagan depictions of a solar disk. Excavations of Roman ruins from southern France with skeletal fragments of rabbits suggested otherwise. Carbon-dating showed that the structures belonged to the medieval period.

Tiny newborn rabbits, called “laurices,” had been a Roman delicacy. It appears that for the medieval French church, this particular ingredient did not count as meat. Like fish, which medieval monasteries raised in large, man-made ponds, little rabbits could be eaten during Lent and other required fasts.

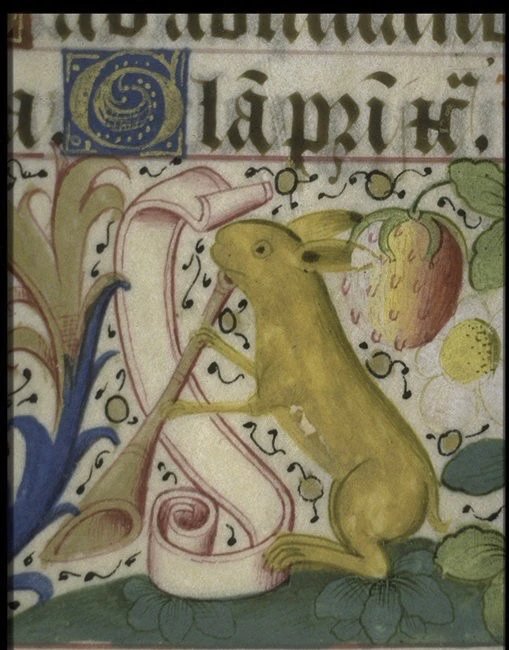

But rabbits did not just appear on the menu. They scamper across the margins of illuminated manuscripts, written and decorated in the monastic scriptorium, throughout the Moyen Âge.

A golden rabbit blows a trumpet in a medieval manuscript from Toulouse. He is part of a scene illustrating the "Annonce fait aux bergers," the annunciation of Christ's birth made to the shepherds.

A rabbit might represent innocence and purity and be associated with Jesus or the Virgin Mary. But more often, monks and their readers turned to rabbits for a touch of irreverence. Rabbits chase hounds. They capture hunters.

In the strict, hierarchical world of the Middle Ages, when every man, woman and child had a fixed role in life from birth, when obedience was often savagely enforced, and rules defined even the color, material, and decorative details of the clothes you were allowed to wear, rabbits turned the world on its ears.

A rabbit and hound fight with swords and shields, from the early 14th-century prayerbook, Le Brevière de Renaud de Bar (Metz, France, 1302-03)

Rabbits served worldly needs, too. “La chasse” had been part of the aristocratic tradition since Roman times. In the medieval epoch, noble French lords raised rabbits, as they did deer and birds, for hunting. Apart from the pleasure and spectacle of the hunt, selling game, hides and fur helped support the costs – a private army, a fortified demesne, fine clothes, generous hospitality and alms, doweries -- of the noble lifestyle. Medieval records show that rabbit farming was a lucrative business. “A single rabbit in the thirteenth century,” writes one historian, “was worth…far more than a craftsman’s daily wage, maybe five times the price of a chicken, and was the equivalent in price of a suckling pig."

Unlike other domestic animals, there is little genetic difference between the tame and wild varieties of European rabbits. Monks and seigneurs seem to have been satisfied with the rapid breeding and easy maintenance of the rabbit as produced by nature. A particularly large and meaty rabbit, known as Géant de Ghent, was known by the 16th century. But it was only in the 19th century, with its delight in new, decorative breeds of domestic animals, that selecting rabbits for size and color became the fashion.

Both the Fauve and the Papillon, two of about 60 regional types of domesticated rabbit in 19th-century France, became registered breeds in the 20th century.

Looking in at the new inhabitants of Madame Francine’s clapiers, I recalled an accidental pet from my own childhood.

Clyde belonged to my best friend’s older brother. Their mother had given each child a rabbit as a fluffy little Easter bundle. Smokey, my friend’s rabbit, had soft grey fur flecked with black and a white nose and paws. You could pick her up and pet her. Clyde was another matter. He had grown into large, white rabbit. He had long claws and a bold temperament. My little friend Parkie dreaded her turn for cleaning the cage. And her brother Cary teased her ruthlessly.

“That’s it,” their mother announced. “Eddy will take Clyde.”

There was a stunned silence. Then Cary shrugged angrily. Parkie began to cry.

Eddy was the hired man. He was kind and a wonder with the garden beds. But it was a known fact that he ate rabbits.

With the implacable sternness of a Roman matron, the children’s mother summoned Eddy immediately.

Ah! Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge! Unlike Titus in Shakespeare’s play, Miss Lucy relented. Eddy obligingly packed Clyde into a crate for his new home. Clyde was to be rescued by me.

My father said he could live in our smokehouse. Clyde, however, needed air and light as well as shelter. With his powerful claws, he rapidly dug under the wire fence we hastily put up. Twice, we caught him and carried him, struggling, back to his pen. But Clyde had tasted freedom and preferred it to caresses and carrots. The third time, he declined to be enticed back to captivity.

He bolted to the old outhouse behind the lilacs. Here, among the bottles and cracked plates that had been thrown under the structure many decades ago, there was a big woodchuck hole. For a while, we caught glimpses of Clyde.

“Clyde is living with the woodchuck,” I cheerfully told my friend.

And then, I am sorry to say, we forgot about him.

“Hmm,” said Madame Francine, pensively. “Quel dommage! He would have made a fine lapin au moutarde, I am sure.”

A bientôt au Chateau, my friend,

Elisabeth

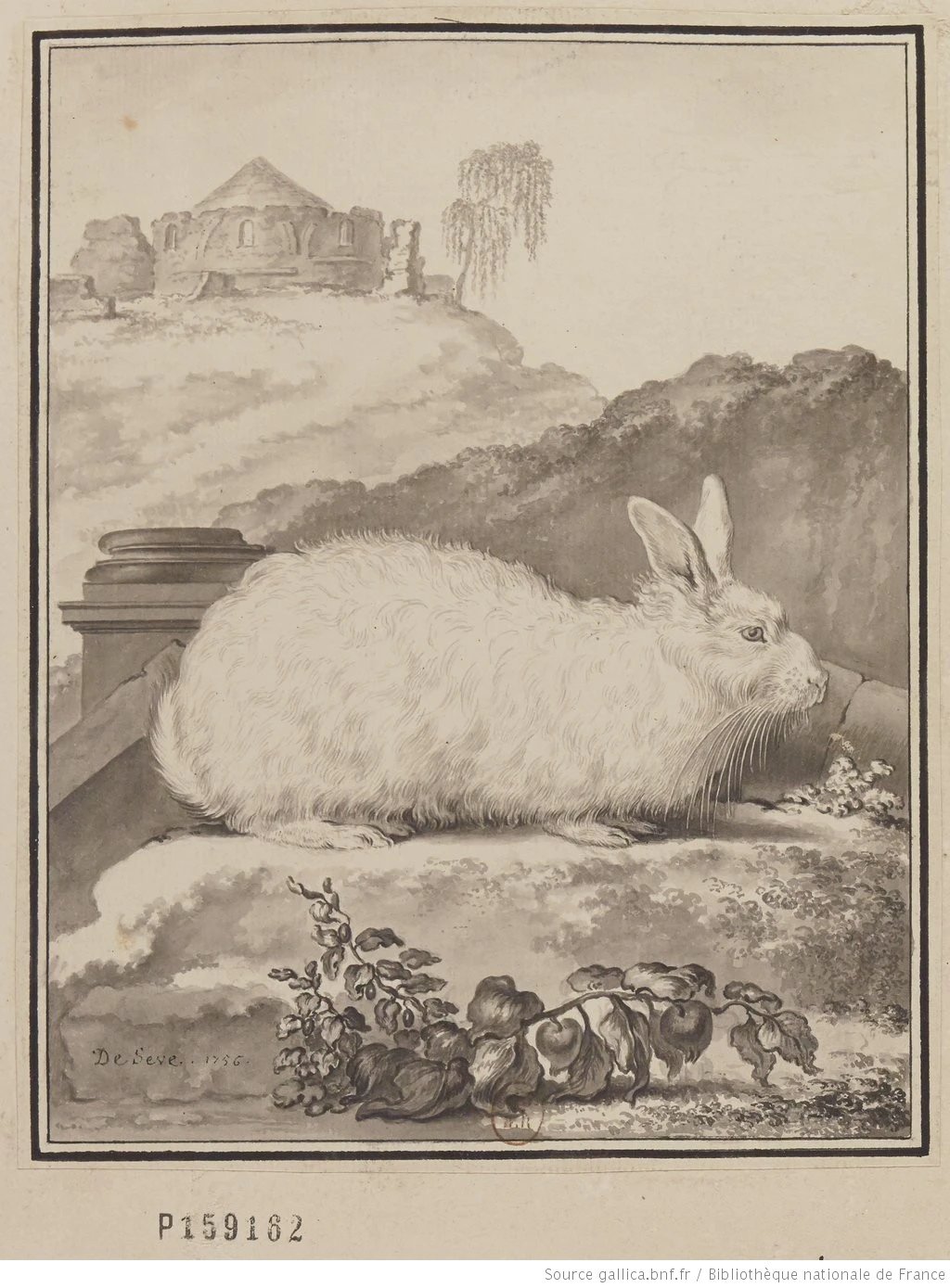

A rabbit, from Buffon's "Histoire naturelle," written and illustrated under Louis XV's patronage. Buffon's massive tomes were widely printed and translated in 18th-century Europe, and reflect the increasing fascination during the Age des Lumières with a scientific as opposed to a predominantly religious understanding of nature.

P.S. As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday or special gathering at the Farmhouse or the Chateau. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.