Cows with spunk

Spring has sprung, young calves leap...and beware the "vache fière"

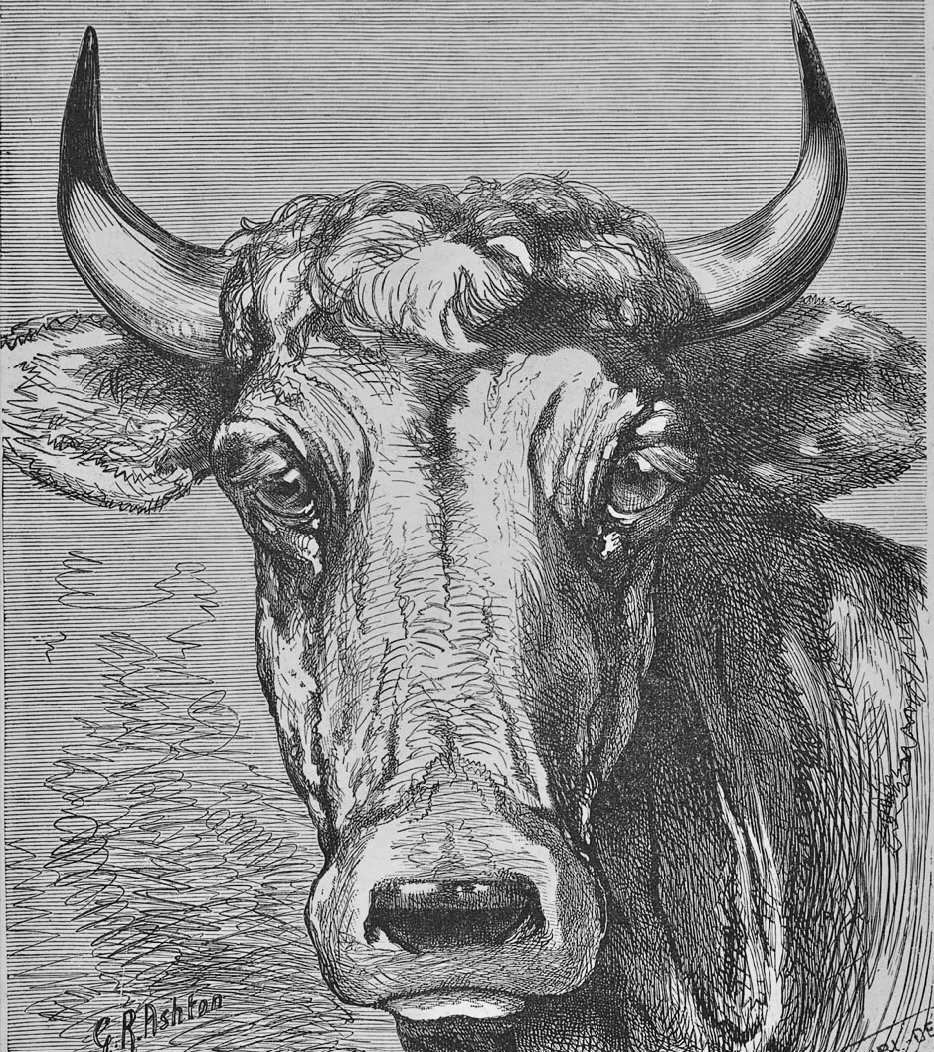

A young Limousine cow out on the grass at Chateau de Courtomer

Chère amie, cher ami,

May has arrived at Courtomer, decked out in white pear blossoms and yellow cowslips. The grass is thick, lush and high.

“En avril, ne te découvre pas d’un fil! En mai, fais ce qu’il te plaît,” remarks Madame Francine approvingly. As the proverb has it, watch out for April, but do as you like in May.

She’s outside airing a duvet, pausing to enjoy the warm spring weather and exchange a bit of conversation. We can see the cattle streaming out into the big pasture behind the Chateau.

The long, cold, wet winter, with its capricious “courants d’air” and winds is well over. Starting last week, Monsieur Jean-Yves and Madame Brigitte turned most of the cattle out to grass. The only bovine residents of the big sheds, or stabulations, back in the basse-cour are a few mothers still waiting to calve.

The young calves revel in unaccustomed freedom, frolicking, skipping, lowering their heads in mock battle.

“And you shall go forth,” says the prophet Malachi, describing the scene from a distance of two thousand years, “and leap like calves released from the stall.

“And,” he adds, “you shall trample down the wicked.”

Wickedness, happily, is far away from this bucolic scene.

The calves’ mothers staidly lower their own heads to the refreshing grass, searching for favorite leaves and tiny flowers amid the varied herbage of the “prairie naturelle.”

The bull, replenished by a winter season of rest and ample nourishment, strolls amid the herd. He snorts and occasionally lifts his head in a lugubrious, libidinous bellow. This is his last season at Courtomer, where he started out as a young fellow of 18 months, three and a half years ago.

Despite Monsieur Jean-Yves initial suspicion regarding his temperament – “fier,” or dangerously proud and possibly wild – our bull has done his service well. Nothing stays the same, though. Soon, he will be sold to accompany another herd on another farm. And his daughters at Courtomer will receive the attentions of the new young bull. He arrived in February and has been learning to mind his manners in a herd of mature matrons and frisky heifers.

“I don’t like that heifer,” commented Monsieur Patrice, the breeder of our young bull, who had come to have a look at the herd at Courtomer a few days ago.

“Fière!”

It was pretty scene. There is a small pasture next to the former milking parlor, a stone barn built a few hundred years ago near the maison de la ferme, the farmhouse. A pear tree grows in the enclosure, and in this season, as mentioned, it is covered with white blossoms. A group of genisses, or heifers, was grazing. One of them exuberantly leapt up and kicked out her hind legs.

Monsieur Jean-Yves, who was standing with us, nodded soberly. He agreed. Having once witnessed Monsieur Jean-Yves being pursued through our field by an outraged cow, I sympathized.

A cow with too much spunk is a liability.

The thought took me back to another time and place, and early experiences with les bovins.

When I was little, we used to visit a boyhood friend of my father’s on his farm in Smithtown, Long Island. The township had been founded through the legendary exploits of Richard Smith and his bull.

Back in the mid-1600s, the chief of the Montauk tribe offered Richard land – as much as he could ride around in a day, on the back of a bull. Richard had helped rescue the chief's daughter from a rival tribe. Smith managed to stay aboard for 10 square miles.

It was cherished family lore, at least to me, that “Bull” Smith was our heroic ancestor. I had heard that our fourth great-grandmother – also an Elizabeth -- had been a “Tangier” Smith from Long Island. And perhaps it was only a coincidence, but Rome’s founder had driven a plow hitched to a bull and a cow to delineate the precincts of the ancient city. These were glorious connections indeed!

To the vision of our ancestress’ possible great-uncle riding a bull around the rolling fields was joined the picturesque experience of the Nicodemus farm.

Besides ducks, chickens, geese and sheep, the family kept a small herd of black and white dairy cows. They were all descended from a venerable matriarch, Daisy. Besides Daisy, there was Daisy’s Baby, Baby’s Baby, and the bull calf, Tarbaby. His father had been an Angus.

The adorable nature of young Tarbaby and the glow of being related to Bull Smith gave me a warm feeling towards bovines.

But one day, as I was playing on the see-saw with my friend Marli, there was an unexpected event. The seesaw was made of an old plank and prone to pinching little legs. It also swivelled unexpectedly and could knock you off. I was concentrating on riding it up and down without incident when suddenly Marli gave a violent shriek. One of the cows had broken out of the pasture. It was thundering towards us. While I looked up in stunned amazement, it leapt over our heads.

I never heard the nursery rhyme “Hey Diddle Diddle” again without picturing the underbelly of the cow, her hooves, and her swishing black and white tail.

Later experiences on our own farm reinforced this lesson about bovine caprice.

Knowing almost nothing about livestock, we bought three cows. Annie, a Scottish Highlander, was pregnant. There was an aged Black Angus, who remained nameless, and a milk cow of indeterminate breed. The Angus constantly broke out of her pasture, ruthlessly charged us, and was quickly sold. Meanwhile, Annie gave birth to a darling little long-haired calf whom we called Bear. We never actually touched Bear; Annie was not so much hot-tempered as dangerously indifferent. Though she was no longer a leaping calf, she had no objection to trampling down the wicked.

A tom-cat we had adopted once tried to drink from her watering trough. The cat, city-bred, with a broken tail, was so tough that our other cat took to living in a tree, like a bird, out of range of his claws and teeth. Greymalkin leaned down for a sip from the old bathtub out in the field. With a flip of her long, curved horns, Annie sent him sailing over the pasture fence. Her imperious behavior extended to the plant kingdom, too. Annie was allowed to eat grass in the apple orchard…until we saw her snapping off lower boughs with the same easy twist of weaponlike horns.

The cattle had been the idea and were under the care of a hopeful farmer. Although John knew even less about cows than we did, having grown up in a fancy suburb, he was an expert on biodynamic principles. These require cow manure. He buried the manure in an empty cow’s horn during the fall, dug it up in the spring and, stirring in a counter-clockwise motion, mixed it with well-water. This concoction was sprinkled on the crops during the waning half moon, he told me.

John had other interests as well.

“When the children are sick, let me know,” he offered. “I’m studying the Theory of the Humours.”

“Don’t let John bleed us, Mama!” begged little Jules, to whom John had been expounding his insights into medieval medicine.

John’s experiences with Annie and our fledgling farm discouraged him so much that he abandoned us on the eve of a major snowstorm. He was afraid of being trapped, he explained from a stop on the highway miles away.

Luckily, I had learned how to milk cows.

Milking a cow as it is meant to be. A pleasant scene depicted by the Norman painter Adolphe Charles Marais (1856-1940), born in Honfleur.

We replaced John with a hard-bitten farm family from Maine, who arrived with a herd of Jerseys. Annie, Bear and the old dairy cow promptly went to auction.

The children were delighted. The Jerseys were used to being led, fed, milked, and brushed.

A long period of tranquil animal husbandry ensued.

We bought a beautiful pure-bred Jersey calf for Viola. As she was reading Greek mythology, she named it Persephone. Jules and Sophie entered various Jersey cows at the county fair. They won prizes. And little Henry helped Mr. and Mrs. Holz make butter and cheese.

Our excursion into cattle raising gave our children unexpected advantages. When it was time for Henry to enter school, he was given a test.

The teacher’s eyes glowed as she explained the results.

“Your son is remarkable,” she assured us. “I showed him a picture of a bird, a cat, and a dog. He knew what they were. But when I showed him a picture of cow, he told me it was a short-haired American milking breed!”

All these experiences are perhaps the reason why keeping a herd of cattle at Courtomer seems like the natural thing to do.

And besides bringing back memories, they are a fine sight, with their ruddy coats against the blue sky and the green pastures, on a sunny day in spring.

A bientôt au Chateau,

P.S. As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday, wedding or special gathering at the Farmhouse or the Chateau. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.

Engraving from a 19th-century French stud-book of the “race Limousine”.