The world in a French thermometer

During the heat wave in Normandy, revelations of a hot day...

Hot days at the Chateau...the education of a thermometer...Above: we bring out the parasols

Sunday, August 7, 2022

Chère amie, cher ami,

I had meant to send you an archive today, but the Canicule is on all tongues these days in France…and I've grown accustomed to writing to you!

“Senegal!” exclaimed our gardener, mopping his brow. He was taking a break, leaning on his hoe. The thermometer, hung on the Orangerie wall, showed a red line to its upper reaches.

We are in the Dog Days, la canicule, of an exceptionally hot summer. A wave of heat has rolled over France and shows no sign of receding.

Even in Normandy, with its plentiful rain and temperatures moderated by Atlantic breezes, 100 degrees Fahrenheit was recorded in the nearby town of Alençon in July. Our wheat and oats ripened several weeks early. The grass in the pastures stopped growing; Monsieur Jean-Yves and his son carry hay out to the cattle to supplement their diet. And Madame Francine assures me that our very same thermometer measured 45 degrees centigrade in the sun.

“That would be 113 degrees,” said Martin doubtfully. Our gardener is an Englishman, transplanted to France from the fens of Lincolnshire.

Madame Francine simply turned her large blue eyes heavenwards, from whence the sun beamed down pitilessly on Martin’s rose beds and the recently planted hydrangeas along the back of the Chateau.

“Nouvelle Cadedonie!” she corrected Martin. In Senegal, according to our thermometer, the temperature registers 50 degrees centigrade. In the French territory of New Caledonia off the coast of Australia, it tells us, the temperature is only around 45 degrees.

Unlike Martin, with his sang froid in the face of our exciting weather and his unmetric vocabulary, our thermometer is French. And it holds a world in itself, a microcosm of natural and human history as viewed through the thick curved glass of its French lens.

Colonies of the former French Empire provide the reference for extreme heat, even if these are not the hottest places in the world. The French held a port in Senegal from 1677, competing with other Europeans for trade in gold, ivory and slaves. In 1853, when the imperial ambitions of Napoleon III stretched from Africa to faraway Oceania, France took possession of New Caledonia.

The reference for extreme cold is Paris in the winter of 1871. The temperature plummeted to -20 centigrade, or -4 Fahrenheit. This was certainly not the coldest spot on the Earth, nor was it the coldest day ever registered in the city. That was actually December 10, 1879, when the temperature in Paris was only -23.9. 1879 was the coldest winter France has ever registered.

But Paris in the winter of 1871 is a byword, at least in France, for severe discomfort.

Besides le grand froid, the Great Cold, the Prussian Army lay siege to the city. Parisians ate the animals in the zoo. Rats were a delicacy selling for two or three times the price of a cat or a dog. And the abnormally cold, hungry winter was followed by a brief and bloody revolution, the Paris Commune.

An American trapped in Paris during the 1871 siege wrote an illustrated account of his culinary and other experiences.

An arrow indicates that “Vins et encres” freeze at 5 degrees below the freezing point of water. Wine actually did freeze on Louis XIV’s table at Versailles. This was during the “grand hiver” of 1709, a catastrophe still mentioned in French textbooks. Young wheat froze in the field, farm animals froze or starved. The last Great Famine, in which hundreds of thousands perished, followed suite.

Our old thermomètre is also a reliquary of French life and habits. Little arrows point to salient facts useful in a variety of circumstances, some of which are no longer à l’ordre de jour.

Bees, for instance, swarm at 35 degrees centigrade. Above that temperature, as many a country man or woman would have known, they will hang on the outside of their rucher, fanning away the hot air with their wings. And if the beekeeper is not vigilant, his bees may swarm away to a cooler abode.

Nowadays, apiculture is a charming if sometimes painful loisir. But until Caribbean sugar plantations developed in the 18th century, honey was the only stable, long-lasting sweetener in Europe.

Another arrow indicates that “vers de soie,” silkworms, flourish at 23.5 degrees.

Here is a glimpse into a forgotten moment – the triumph of la sériciculture. When Philip the Fair installed a French pope in Avignon in 1309, the pontiff introduced the culture of silkworms, known in Italy since late Roman times. Successive French kings, eager for revenue from the silk trade, promoted the raising of vers de soie and the planting of the white mulberry tree upon which they feast.

A child helps gather mulberry leaves to feed silkworms. From a book describing Louis Pasteur's research on diseases of the silkworm.

Raising the cocoons from whose fibers silk is woven became an important aspect of the rural economy in France. It was a profitable enterprise for women and children at home; all the equipment needed was warmth. A little sachet of worms could even be tucked into a bodice, just as one did with baby chicks!

After the disastrous winter of 1709, mulberry plantations replaced devastated chestnut and olive groves south of the Loire. Cocoon production soared to its highest level, 26,000 metric tonnes in 1853, during the heyday of French industrial expansion under Napoleon III. But like the Empire, the French silk industry dwindled away. The last magnaneries – le magnan is the infant silkworm – closed in 1941.

In the domestic sphere, the little arrows on our thermometer tell us about life in the France of yesteryear. The proper temperature of a bath is a tepid 32. The temperature inside a house is only 15. The "chambre des malades", the sickroom, is to be kept at 22, a little under 72 degrees Fahrenheit.

Madame Francine nodded in approbation.

“On ne jet pas l’argent par les fenêtres!” she commented. “We don’t throw money out the windows!”

Remark, said Madame Francine, with a flourish of her index finger in Martin’s direction, the Orangerie must be kept above 7.5 degrees. Otherwise, she added, sternly, motioning to the arrow on the thermometer, the lemon trees will wither in the frosty air.

“Yes, well, it’s not very cold just now,” replied Monsieur Martin impassively, putting away his damp handkerchief and moving off toward the bassin of the canal.

“I shall see about the young waterlilies.”

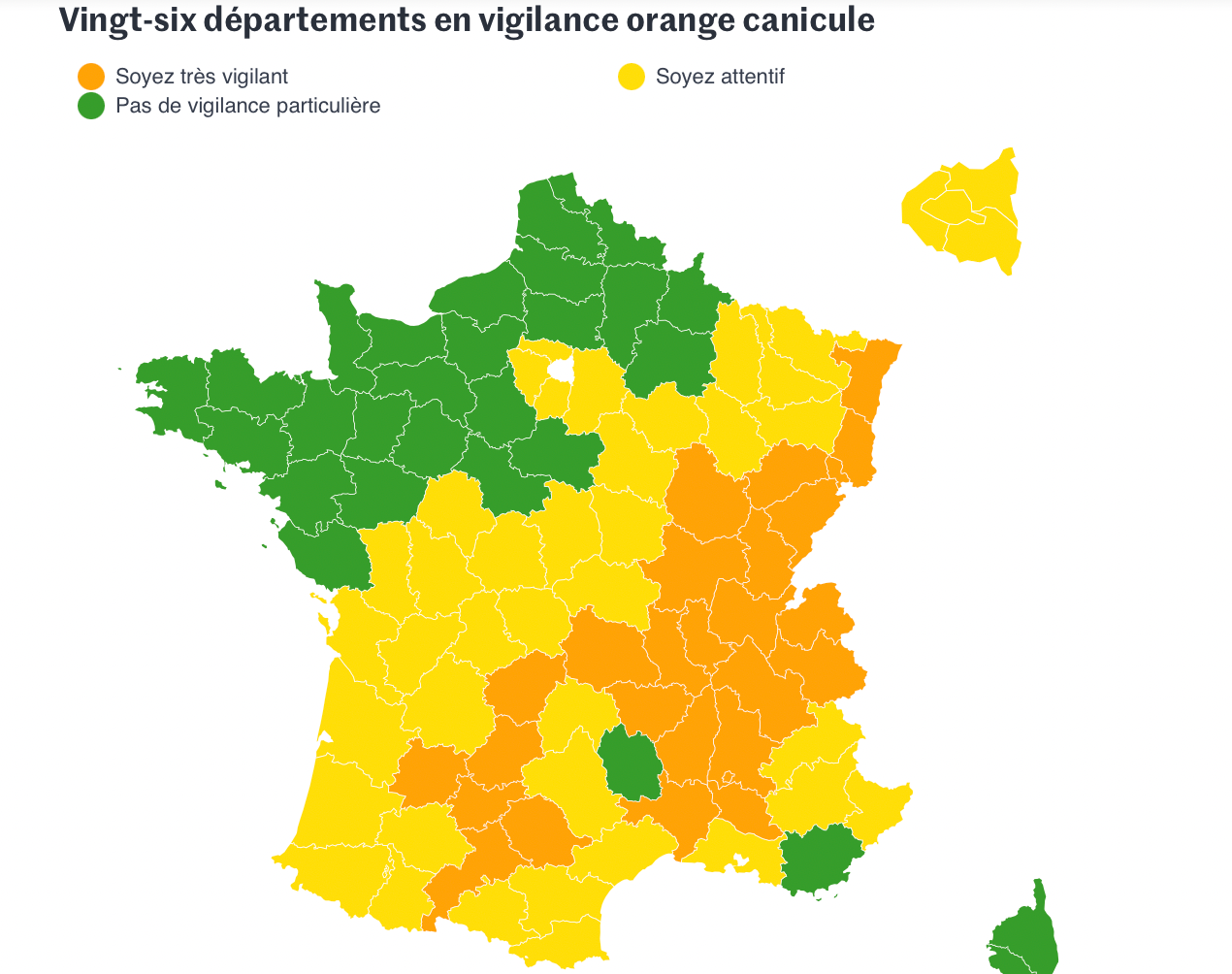

Monsieur, rattling today’s issue of Ouest France, announced the latest bulletin on the canicule.

“Pas de vigilance particulière,” he quoted, reassuringly.

A bientôt au Château,

Elisabeth

While the map of France shows much of the country colored in various shades of yellow and alarming orange, Normandy retains its usual shade of green…with temperatures in the days to come around 80 (Fahrenheit).

P.S. As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday or special gathering at the Chateau, the Farmhouse or both. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.