Serenade indochinoise

Serenade of Indochina...a moment in time...

Adhémard Leclère took this photograph of a dancer at the crowning of the king

Friday, February 4, 2022

Chère amie, cher ami de Courtomer,

On a darkening winter afternoon, the cobbled streets of Alençon gleam in the bright light from shops and the faint beacon of the cathedral’s tall belfry. These stones have been polished over centuries. The hurrying feet of shop keepers and of customers rushing home, the easy gait of the window-shopper and the flâneur, the pieds de plomb of the reluctant écolier and the joyful skipping of little children, the measured march of the academic and the priest, and the relentless rhythm of armies have smoothed the rough corners of these unfeeling pavés.

We are deep in the heart of Normandy, where half-timbered medieval houses lean over the sidewalks next to ornate Renaissance houses, and palatial 18th-century buildings are set sedately behind elegant iron railings. Here, the great gothic cathedral has been disfigured and transformed by natural disasters and human intervention, and the great stone towers built by William the Conqueror to fend off the king of France loom above a municipal parking lot.

Alençon represents a thousand years of French history and culture, from Viking conquest to the present day. But in the midst of this jostling mélange is a curious portal to an entirely different place. This is a collection of several thousand objects brought to Alençon from Cambodia in the early 20th century.

Adhémard Leclère, born in Alençon in 1853, set out for Southeast Asia in the 1880s. He was the son of a skilled tailor, an enthusiastic participant in the learned societies of his time, and an ardent socialiste radicale. He was also a colonial administrator.

None of these aspects of his life were contradictory. He came of age in the transformative latter years of 19th-century France, when a combination of egalitarian ideals and rapid economic growth offered upward mobility to men of all walks of life and also fostered radical political movements. It was a period of optimism regarding human progress and ingenuity, of faith in the rights of man…and a period of relentless colonization linked to an equally enthusiastic optimism regarding the destiny of one’s own nation.

Two years before Adhémard’s departure for Indochina, the great Jules Ferry, father of public education in France, had given his stirring discours on the colonies:

“…qu'elle [la France] ne peut pas être seulement un pays libre, qu'elle doit aussi être un grand pays exerçant sur les destinées de l'Europe toute l'influence qui lui appartient, qu'elle doit répandre cette influence sur le monde, et porter partout où elle le peut sa langue, ses moeurs, son drapeau, ses armes, son genie.” (Applaudissements au centre et à gauche.)

“Liberté” was not enough; France must seek greatness, said Ferry, speaking to the Assemblée générale of 28 juillet 1884. And, since this was the late 19th century and colonies seemed to promise both greatness and great riches, France must build her colonial empire. Perhaps Ferry viewed colonization he viewed education:

“Je répète,” he went on the say, “qu'il y a pour les races supérieures un droit, parce qu'il y a un devoir pour elles. Elles ont le devoir de civiliser les races inférieures...”

France had a right and a duty to impose its civilisation on “inferior peoples.”

Ah! It is heartening to report that many of Ferry’s colleagues shared the future President Clemenceau’s opinion:

“C’est très douteux.” Very doubtful.

But Adhémard Leclère was not troubled by doubts. The flourishing commercial and trading city of Saigon, in Cochinchine, had been captured by Napoleon III’s army when Adhémard was a mere child of six. By 1871, all of Cochinchine was a French colony. By 1886, when Adhémard sailed for Cambodia, the country was a Protectorate of the French Republic, along with Amman and Tonkin, today’s Vietnam and Laos.

Civilization was marching on!

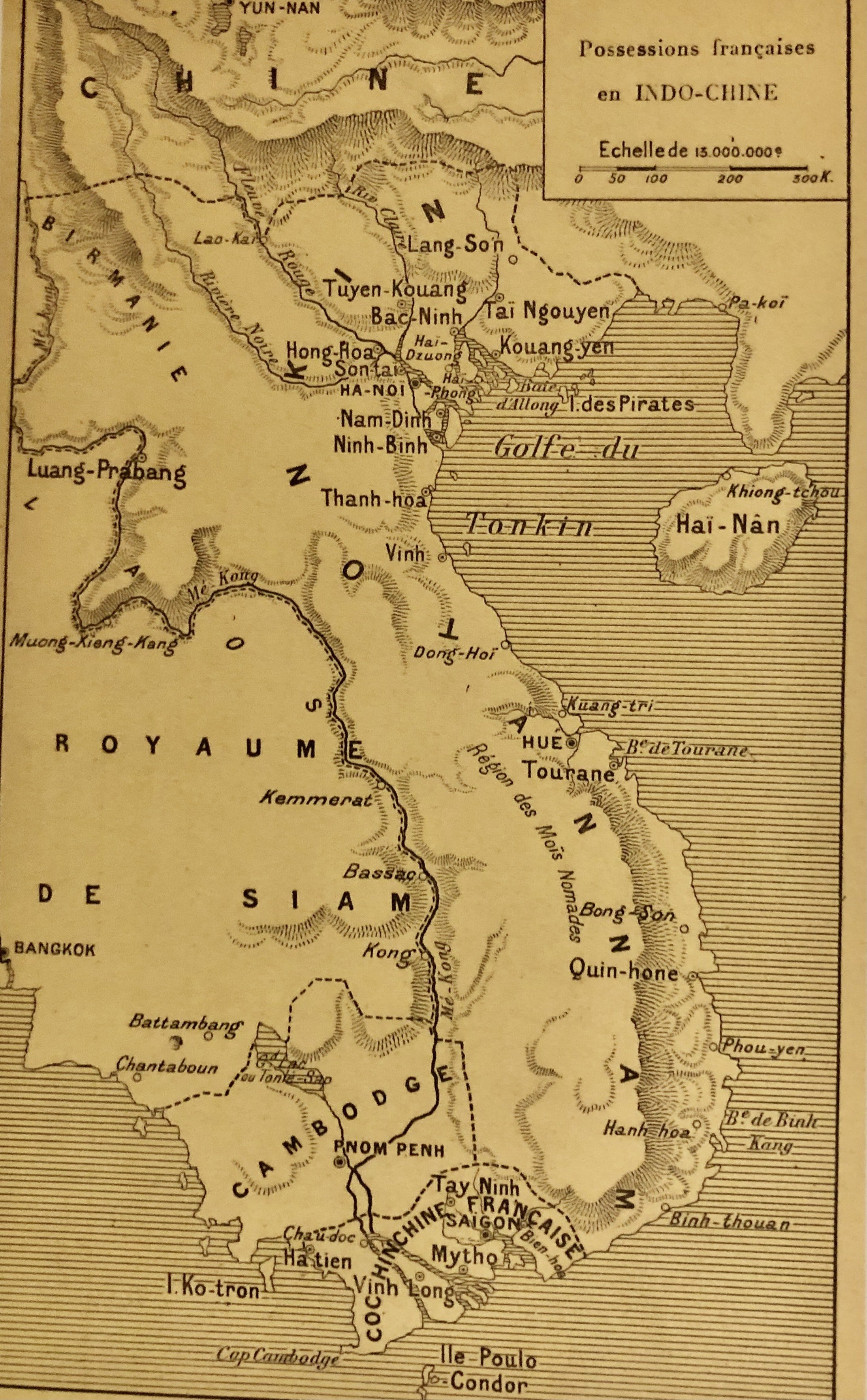

L'Indochine française when Adhémard set out for Cambodia

Over the next half century, through the glory days of the 1930s, rice production in Cambodia increased exponentially. It became one of the largest producers of rubber. Irrigation and modern farming methods were introduced. Asphalt roads connected the agricultural central plain to the coast. There were hospitals and schools, and a university in Hanoi. Except for a few brief rebellions, sparked by cultural misunderstandings rather than deep resentments, it seemed clear that la presence française was a positive force for improvement.

Adhémard’s life in the colonies had its difficulties. His first wife died in childbirth, far away in France where she had returned to have their twins. His second wife drowned in a boating accident on the Mekong. And he was never promoted beyond the post of “Résident.”

But Adhémard was what is called an “esprit curieux,” a man with an inquiring mind. As district resident, he made his rounds on horseback through villages, along rivers, in the rain forest of the high plateaux toward the Thai and Vietnamese borders. He frequented both royal palaces and the camps of hill tribes. And he assiduously took notes of what he saw, discovered and thought.

Puppets and masks used in theatrical presentations of the Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana, from Adhémard's collection at the Musée de Beaux Arts in Alençon

Inspired by the French rediscovery of Angkor Wat, he conducted explorations and excavations. He copied inscriptions and transcribed rare documents. He collected textiles, ritual objects, weapons and tools. He invented a method for writing the Khmer language in European characters. He wrote about contemporary customs and the royal household, native theatre and literature, and Khmer legal codes.

In 1910, Adhémard retired, moving back to Normandy. It must have been strange, after 25 years in the Far East, to walk those cobbled streets, to feel the damp chill of winter, to see the ground white with hoar instead of a humid morning mist rising over the watery rizières.

Most strange must have been the indifference to his remarkable experiences. His carefully collected notes did not interest the “érudits” of the Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, based in Paris and almost exclusively fascinated by the ancient power and sophistication of India and China. A few of his findings went to the Musée Guimet in Paris, but the vast majority of his life’s collecting, including an archive of 500 photographs and thousands of manuscript pages, repose in the Musée de Beaux Arts in Adhémard’s natal city of Alençon.

“Et maintenant, c’est fini,” begins the last emission from Radio France-Asie in 1956, two years after the final French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. “And now, it is finished.”

“On ne vie pas sur des souvenirs,” continued the announcer. “We do not live on memories. We hope, however, that we will stay in your hearts as you will stay in ours.” His voice broke. At the end of the announcement. the staff sang Auld Lang Syne in French:

“Ce n’est qu’un au-revoir, mes frères.”

“It’s just a good-bye, my brothers.” But it was a final farewell.

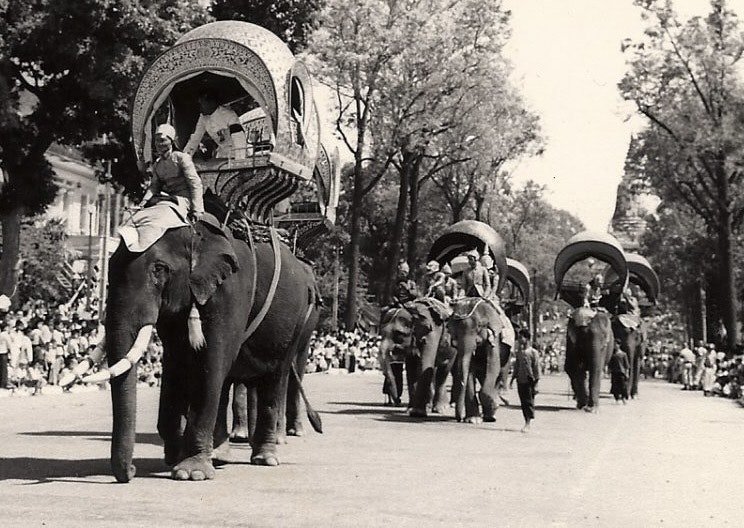

A far cry from the streets of Alençon, the wide boulevard in early 20th-century Phnom Pehn, capital of the Protectorate of Cambodia, during a religious festival

Although his contemporaries may have thought little of it, Adhémard’s collection and archive preserved a heritage and a moment in time that was as doomed as the French colonial regime.

The Indochine française that Adhémard Leclère left behind in 1910, where his young wife was buried and he had become Adhémard “le Khmer,” expert on all things Cambodian, was finished.By the end of the 20th century, war and a new and devastating idealism had put a stop to the high-minded aspirations of Jules Ferry. The Bibliothèque nationale was empty of books; the fields were full of bones. A quarter of the population had been killed during the regime of the communist Khmer rouge, and much traditional life in Cambodia had been eliminated as well. The royal palace and the shadow puppets were silent. And many of the hill tribes whom Adhémard had visited, photographed and studied had almost disappeared.

After his retirement, Adhémard Leclère wrote a few cranky articles on Norman antiquities for local learned societies and a slim, self-published volume on the theatre at Alençon in the 18th and 19th centuries. He died seven years later, in 1917.

Serenade indochinoise…

Je l’entends très souvent…

Près des rizières de Chine

Et l’amour pour toujours…

Serenade indochinoise

Fait oublier bien des larmes

Donne la vie plus de charme

Un charme qui vous prend l’âme

Serenade indochinoise…

Tu me prends tendrement, tendrement, tendrement…

Serenade of Indochina…

I hear you often…

Beside the fields of rice

Love is for ever

Make me forget my sorrow

Fill my life with your charm

A charm to captivate my soul

Serenade of Indochina…

You touch me tenderly…

Perhaps Adhémard, in the strange exile of his retirement, listened for a “Serenade Indochinoise.” Amid the photographs and objects he gave to the Musée d’Alençon, you may hear its plaintive melody yourself…

A très bientôt, chers amis!

Elizabeth

P.S. Serenade indochinoise was first sung in 1943 by the “chanteur de charme,” Jean Lumière, when France was occupied by Germany and the Japanese Empire was ruling in Cambodia. La nostalgie for l’Indochine française and past glories must have been at a height.

P.P.S. Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your family vacation or special gathering at the Chateau. for this year through 2024. They can suggest activities in the surrounding countryside and towns for all ages and seasons. Please feel free to call or write us.

The streets of Phnom Penh in 1973, while being invaded by the Khmer rouge