New Year's "voeux" on a pheasant

From the woods to the table...our neighbour brings us "un p'tit régal"

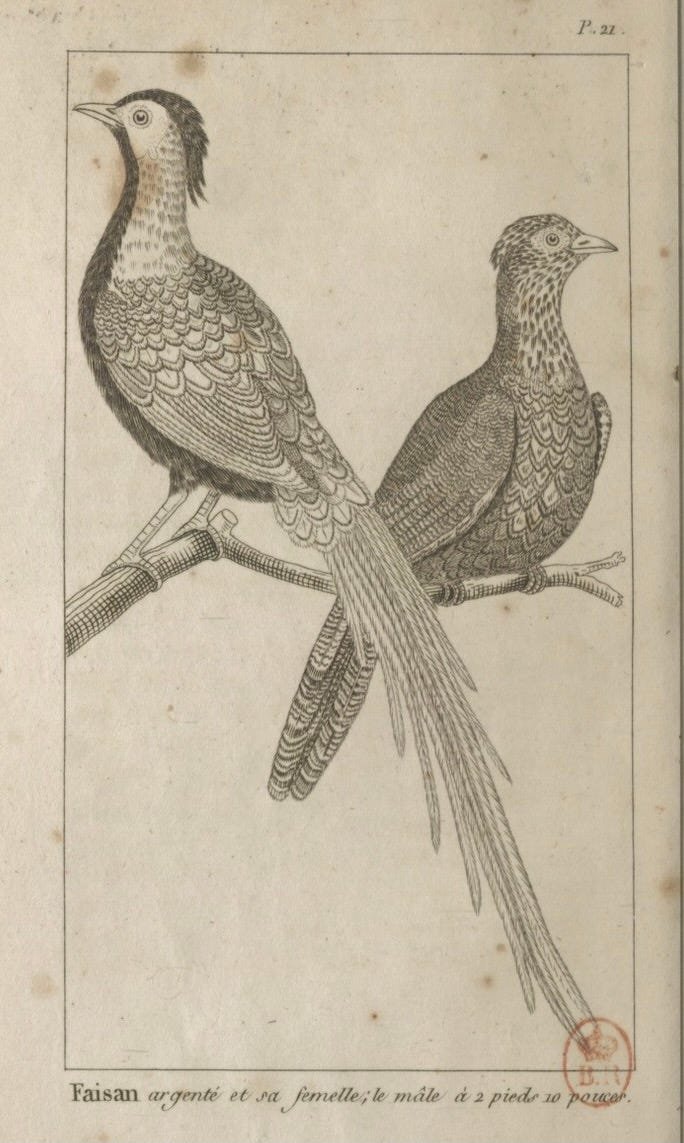

Above: a page from an early 19th-century treatise on pheasants, swans, peacocks and parrots, among other birds (Traité des oiseaux de chant, des pigeons de volière, du perroquet, du faisan, du cygne et du paon, Collection BNF)

Last week, just after Christmas, our neighbor stopped by. A man who is always in a hurry, he didn’t want to come into the kitchen. He had a little present for us.

“Un p’tit regal!”

With a proud smile, he held up a well-worn red plastic shopping bag. Several feathers, the color of glossy chestnuts and rich mahogany wood, striped with bands of black and white, protruded out of the top.

“Ah ah!” he exclaimed, pleased by my air of stupefaction.

“Des faisans pour la Saint-Sylvestre!”

Pheasants for New Year’s Eve!

Taking the bag, I peered inside. Nestled limply together, necks looped together with orange baling twine, a brace of pheasants lay loosely entwined in luxuriant plumage.

“I’ll hang them in the grange,” offered our friend. “They will stay thus nice and cool while they mortify.”

“No more than a week!” he called out, as he turned to go.

I had seen that the birds were not yet plucked. Was there more to do, I asked, skirting around the word “vider,” meaning “to empty” the birds. Georges stopped momentarily. Of course not. Everything must remain intact until we were ready to take the birds down and eat them.

“Bon appétit!” he cried, slamming the door of his camionette and starting the motor.

“Well,” stated Monsieur, watching Georges put on the brakes as he veered around the moat. “I imagine it isn’t too difficult. If I were you, I’d look up plucking a pheasant on Youtube.”

He went outside to fetch more wood for the fire. Returning, he reported that Georges had suspended the birds, safely protected in their bag, from a rafter. A “courant d’aire,” a slight draft, would keep them cool and dry.

The days went by. I cooked one meal after another for my assembled family. We ate salmon, roasted ribs of pork, and left-over goose with chestnut and prune stuffing from our Christmas meal. The pheasants continued to se faire faisander, or to decompose gently while suspended from the rafter.

Never having plucked or drawn any kind of bird, I tried not to think about them.

“It’s been six days,” announced Monsieur finally. My husband went out to the grange and returned with the shopping bag and its feathery contents. He set up a trestle table outside.

Our pheasants

I opened the bag.

Jean Brillat-Savarin, the early 19th-century gastronome, recommended hanging a wild pheasant until “le verdissement de l’abdomen,” until its abdomen turned green. His fellow “gourmand” and food critic, Alexandre Grimod de la Reynière, recommended hanging a pheasant by its tail feathers until it fell to the ground, when it would be properly “ripe” and endowed with the prized “haut goût,” strong flavor.

Le faisandage, scientifically speaking, is the result of “une fermentation bactérienne.” It is also called “la mortification,” a natural and time-honored method of tenderizing game.

When I was a child, an unlucky pheasant flew into the bay window of the dining room. It lay still on the grass.

My mother leapt from the table and hurried outside.

“Wonderful!” she exclaimed, holding it aloft. The bird had broken its neck. She carried it down the cellar stairs, where it would hang, she informed us, until its feathers pulled easily away.

As I did not participate further in the bird’s journey to the table, I knew nothing more about le faisandage.

Happily, our birds had not rotted off the string that held them to the rafters, and I was relieved to see that their abdomens were not green.

I put on an apron and wondered how to pluck them.

“Maybe it’s like that song, “Alouette,”” suggested our son Jules, who was visiting from Dublin with his family. “Start with “le bec” and go on down to the tail.”

“Alouette, gentil alouette,

Alouette, je te plumerai.

Je te plumerai le bec…” he hummed.

“Lark, pretty little lark,

Lark, I will pluck your feathers,

I will pluck your beak…and your head, and your feet, and your wings, and your back, and your tail!”

But a helpful youtube video showed that instead, one must start from the tail up to the neck, row by row, feather by feather. One holds the skin taut with one hand, and plucks with the other. Otherwise, advises the video, the delicate skin might tear. And it is the skin that helps keep the bird juicy while it roasts.

I tugged one of the tail feathers, which resisted.

“I’ll help you, Maman,” said Jules, coming outside.

Companionably, in the cold winter sunlight, we set to work.

The beautiful feathers, soft as silk, blue and green, tawny gold and brown, white and somber black, mottled, striped, and spotted, accumulated in a tin bucket.

Pheasants are exotics amid the sober native birds of France. Centuries ago, the Greeks brought them to the Classical World from a place they called Colchis, on the east bank of the Black Sea. There, Jason and the Argonauts, searching for the Golden Fleece, found them along the river Phasis. The Romans named them phasianus, the bird of Phasis. They kept them in cages, the better to admire their gorgeous plumage. They carried them around the Mediterranean and throughout the Empire.

The Romans hunted pheasant: a 5th-century mosaic pavement from Syria, then the Eastern-most province of the Roman Empire, shows a hound on the hunt, an African lion and a plump pheasant. Musée du Louvre

In a 2nd century A.D. account of a fabulous procession given in Egypt by “that most admirable of all monarchs,” Ptolemy Philadelphus, we read of “150 men carrying trees, from which were suspended birds and beasts of every imaginable country and description; and then were carried many cages in which were parrots and peacocks and guinea-fowls and pheasants.” The extraordinary procession also included 600 boys in white tunics, 500 maidens in purple, wagons heaped with precious objects, jewels, gold and silver, quantities of wine, elephants, camels, Moluccan hounds, “women of India” dressed as captives, men dressed as gods, and more.

Stupendous displays of wealth were a feature of the classical world. Kings and generals, emperors and aristocrats expressed the vigor of their power in processions, pomp, and feasts – and the pheasant lent its fine plumage and exotic origins to the spectacle.

Though the Roman Empire came to a dire end in the West in 476, the pheasant prospered. At about the same time as the Vandals and Goths sacked Rome in the 5th century, a Roman chef described how to make dumplings from “lightly roasted choice fresh” pheasants in De Re Coquinaria. Under the new Barbarian lords of France, pheasants were raised in pens, like hens and other domestic fowl. In the 1200s, Saint Louis released pheasants in the bois de Vincennes of Paris, where he hunted them on horseback with falcons.

In 1454, a year after the Turks captured Constantinople and with it the last outpost of the Roman Empire in the East, Philippe de Bourgogne gave a sumptuous feast in Lille. This was one of the most extravagant spectacles of the Middle Ages in France. It was a final vestige of the tradition inherited from Imperial Rome.

Ptolemy might have shrugged, but the guests – the noble compagnons of the duke’s order of the Toison d’Or and their ladies, other dignitaries and the general public – were amazed! Spread out on tables were an artificial lake and model ships, a forest with a lion and other wild beasts, a church ringing its bells, a model of Philippe’s ducal château spouting orange-flavored water. There was a mechanical tiger fighting a snake, a “sauvage” on a camel, a buffoon on a bear, and a windmill. Out of a pie popped 28 musicians. During interludes, there were dancers, acrobats, jugglers and a play of Jason and the Golden Fleece.

Finally, a giant appeared, leading an elephant upon which was seated a lady representing the Holy Church. She carried a pheasant on her wrist. She wept for the loss of Constantinople. Two chevaliers of the Toison d’Or carried the pheasant to the duke. According to ancient custom, they declared, a noble bird is offered to the noble host after a great feast, and a vow is made.

The duke rose to his feet and swore “à Dieu, mon Créateur, à la glorieuse Vierge Marie…to the ladies and to the pheasant,” that he would send a crusade to liberate Constantinople.

Despite his good intentions and the pheasant, Philippe de Bourgogne never attempted to deliver Constantinople. It was the end of an era. The Roman Empire had finally collapsed, the Middle Ages, according to historians, was about to end, and Philippe de Bourgogne was preoccupied by war with the king of France. But the glorious occasion is known to posterity as the “voeu du Faisan,” the Vow of the Pheasant.

“Naturally,” commented Jules, “the pheasant was chosen because of the bird’s association with Jason and the Golden Fleece, the “Toison d’Or.” The duke of Burgundy wished to link his magnificent court and territorial ambitions to the golden age of Ancient Greece and its heroes.”

Jules learns to pluck a pheasant

Quite so! But only half of my bird was plucked. The sky was darkening as the winter afternoon waned into night. Our fingers were growing tired and stiff. And it had begun to rain in small cold drops.

Most of the feathers came out swiftly, although the tail feathers with their thick quills required a firm grip. We set these aside with the wings as a tribute to the fine birds.

Finally, the pheasant’s thin, delicate skin was exposed. A few tufts of white down marked the beginning of long silvery legs and sharp-clawed feet.

The crop, at the base of the pheasant’s neck, must be carefully removed by making a small nick at the base of the throat and lifting out the sack containing the bird’s last meal. My pheasant had eaten grass, now well-decomposed, and a few plump kernels of oat. Jules had been less deft with his knife. The contents of an ample meal of grain spilled over the pheasant’s breast. But no matter; this was easily washed off.

The viscère was another matter. The youtube video showed one hefty, tattooed arm holding down the carcass and the other slitting the carcass neatly up to the beginning of the breastbone. One feels around the cavity with two fingers and a thumb and draws out the bird’s innards in one clean tug. Then you reach back inside to detach the heart. To my great relief, the operation was successful. Nevertheless, an odor haunted the cavity. Jules and I agreed it must be the result of proper hanging. We washed the pheasants out under running water.

I roasted the pheasants that night. The platter, ornamented with roasted lemons, cloves of garlic, and sprigs of rosemary, was placed in front of my family. We all looked at it uneasily. But Monsieur picked up the carving knife. Jules and I gazed at each other staunchly.

A new experience for a new year.

In the end, the pheasants, hunted by our neighbor, hung, plucked and drawn by our own hands, were “un petit régal.” Henry had seconds. Edward ate some cold with mayonnaise the next day. And over the carcass, holding aloft a glass of champagne, we made our own vows for 2023. Though not as grandiose as those of 1454, we hope they will be more durable!

Bonne année, chers amis!

Elisabeth

Jean-Baptiste Oudry's portrait of a bird hound with pheasant in flight. By the 18th century, pheasant were well established in France. Musée de Lille

P.S. In case you’d like to try roasting your own pheasant, this is my method:

Roast Pheasant

The pheasant cooks for a short time at a hot temperature. It can be served slightly pink.

I put mine in a preheated 200 C/400 F oven for 45 minutes, or until the leg joint moved freely. I took the bird out of the oven to rest for 10 minutes before carving.

In a roasting tin, I surrounded the pheasant with a handful of garlic cloves in their skin, bruised with a rolling pin, plus sprigs of thyme and rosemary, bay leaves, and a lemon cut in half. The lemon provides moisture while the bird cooks. I salted and peppered the bird inside and out, and then covered the breast generously with pork fat (I had saved the fat from a pork shoulder roasted a few days before). My neighbor drapes her pheasant in “crepinette,” or pork caul, which she buys from the butcher. And many cookbooks recommend fatty bacon. The idea is to stop the delicate breast meat from drying out.

I served the pheasant with thinly sliced potatoes and more garlic cloves roasted in a little goose fat, and steamed green peas from our summer harvest. A dab of chutney or gelée de groseilles, currant jelly (not too sweet) is a delightful addition. Cold left-over pheasant is good with a dollop of mayonnaise.

The remains of the feast

* *

As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your own holiday or special gathering at the Chateau or just to rent the Chateau, the Farmhouse or both. We have just a few openings for the end of this year and in 2023, and are taking bookings for 2024 and 2025. We look forward to hearing from you. A bientôt!