A Temple to a Heroic age...A Papal Bull, a Defiant Dame and the Huguenot nobles of Courtomer

before renovation, the Habitable was a home for cattle

Dear Friend,

“Puisque nous sommes partis à la pluie,” Monsieur Jean-Yves reminded me, les bovins have entered their quartiers d’hiver. The autumn rains started last week. The cattle are being moved into winter quarters under shelter.

Plodding single-file through the damp pasture, past the dripping trees, and over the little bridge that spans the Risle, our laughing stream, the cattle followed their doyenne – the senior cow -- into the stabulations of the basse-cour.

Here they will stay, on a dry bedding of fragrant homegrown straw, until the pastures dry out next spring.

The bull followed toward the rear, swinging his hefty haunches and his admirably muscular neck in majestic rhythm.

“And what about the Papal Bull?” Clara reminded me, following a natural train of thought.

Liam and Clara are helping to blanch chestnuts in the kitchen, where the windows give on to a fine view of the back pastures and their occupants. Marrons glacés, sugar-soaked chestnuts, are as traditional here at Christmastime as home-cooked foie gras and a roasted turkey. And we start the week-long preparation process by plunging them in boiling water to soften the shells for peeling.

At ten, Clara is a fount of erudite information, generously shared. She paused, paring knife in hand over the pile of peeled chestnuts. A Papal Bull, she told her brother, is not an animal. “Bull” comes from the Latin “bulla,” meaning a seal. The Papal Bull is a document folded and closed with the pope’s seal impressed in metal.

We had been to Laval, where we had been captivated by the story of Guyonne, Dame de Laval, and her connection to a distant past at Chateau de Courtomer.

Guyonne’s husband, Clara reminded us, had obtained a Papal Bull against his wife in 1557. She had refused to return to her husband, thus depriving him of his conjugal rights. Obligingly, Pope Paul IV excommunicated the willful lady.

Guyonne’s husband had already imprisoned her once. He was intent on usurping the power and dynastic wealth she had inherited on both her mother’s and her father’s side. He had even taken the name and title of Guy XVIII, comte de Laval, which had been the title of Guyonne’s uncle and now belonged to her by inheritance.

Medieval society was a complex network of reciprocal obligations, determined by social rank, legal status, and raw power.

Flouting those obligations, as Guyonne had done, was a grave matter. On the other hand, excommunication could release others from their duty to the sinner. The Church held that the pope could “absolve subjects from their fealty to wicked men." This was a dangerous position for Guyonne, who needed the knights in her domain to fulfill their feudal duty to protect her.

In ordinary times, the Holy See might have stood with Guyonne against her predatory spouse. But the 1550s in France, as elsewhere in Europe, were times fraught with uncertainty and danger.

The dissident followers of Martin Luther, Jean Calvin, the English sovereign and various German princes contested the authority of the Church, including its pope, priests, saints and central doctrines.

The printing press, invented about a hundred years before, sped the transmission of new ideas. Literacy was on the rise as books became readily available. Not only did educated people read the Bible for the first time, they could read books of poetry and science, history and philosophy.

And everybody, literate or not, could understand the suggestions made by quantities of nasty cartoons now being printed and distributed.

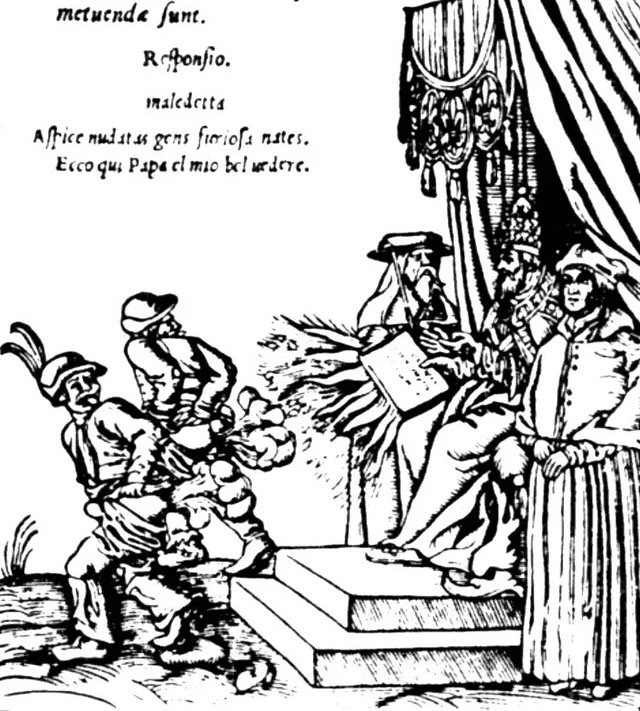

Martin Luther stands by sternly while two peasants demonstrate scorn for the Papal Bull of excommunication. A broadside of 1545

The authority of ancient institutions, from the Church to the legitimacy of kingship and the power of the aristocracy, was open to dispute as never before.

One priest at Alençon, in our corner of Normandy, went so far as to write that

“both men and women will understand the Scriptures, and women will be bishops, and bishops will do women’s work. For they will preach the Holy Scriptures and the bishops will embroider with the girls.”

He also denied the authority of the pope.

Perhaps it is hardly surprising that Guyonne ignored the Papal Bull and promptly joined the Protestant rebels. In addition, her sister Claudine was married to one of the most prominent Protestant nobles in the realm, François de Coligny d’Andelot.

The Protestant chief, François de Coligny, took Guyonne under his protection. His son would later inherit her title.

The French Wars of Religion, pitting the Protestant and Catholic nobility against one another with the king uneasily sandwiched between them, would begin five years later with the massacre of Protestants worshipping in a grange. But already, a general tolerance for free-thinking had ebbed into active discrimination against those calling themselves les réformés, the reformed Catholics.

The Affaire des placards, taking place a quarter century before, had laid the groundwork. Unsigned “placards” were posted throughout France accusing the Church hierarchy of blasphemy. In a postscript, the writer menaced those who supported the infamous messe papale: “leur regne sera détruit à jamais!” One of these posters was plastered upon the very door to the king’s bedchamber. The reaction, particularly on the part of King François 1er but also on the part of indignant mobs, was violent.

Protestants claimed that a direct dialogue with God made priestly intercession in the sacraments of communion and absolution unnecessary. Now they were suspected of claiming the same independent rights in politics – of wanting to overthrow the king. And it was partly true; the French nobility was traditionally suspicious of growth in royal power.

The liberty of conscience demanded by Huguenots was akin to the noble idea that the aristocracy should be independent of common servitude. The calling of the nobility was war, not plowing or herding, buying and selling. Their fate might be violent death, but not servility. Better to lose one’s honor than to betray one’s conscience, as Michel de Montaigne wrote in his famous Essais.

“Toute personne d’honneur choisit de perdre son honneur plutôt que de perdre sa conscience.”

The brutal conflict that followed the Affaire des Placards was known as the Age héroïque, the Heroic Age of Protestantism in France. It was particularly heroic in the West of France, where powerful noble families -- the Condé, the Rohan, the Coligny, the La Noue, and the king’s own brother, the duke of Alençon -- took arms to defend their freedom of worship and their lives.

The massacre of Wassy in 1562. The troops of the Duc de Guise attacked Protestants in a rural grange larger but not unlike the Temple at Courtomer.

At Chateau de Courtomer, our own châtelains had also converted to la Réforme. They were allied by marriage to leaders of the Protestant resistance, like La Noue. And they were related to Guyonne de Laval through her father’s family, the Rieux…although as Monsieur Xavier pointed out, this was through a “fils naturel.”

Now known as the “comtesse huguenotte,” Guyonne de Laval herself became one of the heroic figures of the doomed revolt. A decade after her excommunication, she took part in the “Surpise” of Meaux. Along with her brother-in-law François, his brother Admiral Coligny, and Louis, prince de Condé, she plotted to kidnap the king of France, Charles IX, and his mother. The enterprise was a failure. Guyonne was condemned to death, with her coat of arms to be dragged through the streets of Paris and confiscation of her worldly goods.

She escaped these final indignities. Her tumultuous life came to a sudden and apparently natural end at the age of 43 on December 13, 1567, the same night that the city of Laval organized a procession to ask God’s help in extirpating Protestantism. Despite the excommunication and her adherence to “calvinisme,” Guyonne was quietly slotted onto a shelf with her Catholic ancestors, the preceding comtes and comtesses de Laval, in their family tomb in Laval. Her title and vast properties passed to her nephew. Protestant to the end, he died, along with his three brothers, of wounds received in the battle of Saintonge during the Wars of Religion.

During the long years of increasing restrictions, discrimination, persecution and les Guerres de Religion, the family at Chateau de Courtomer also remained Protestant…while serving the kings of France in war.

A century later, a younger generation yielded at last. Louis IV had revoked his grandfather’s Edict of Toleration…and posted dragoons in private homes to ensure compliance.

Nevertheless, the “habitacle,” as the Protestant temple of Courtomer is called, still stands. One of the few surviving examples of 17th-century Protestant worship in France, it covers the tombs of a faithful noblesse huguenotte…and ensures that this moment in history is not forgotten.

At top of Letter: before renovation, the Habitable was a home for cattle. Here, under the snow.

Liam and Clara were tired of peeling chestnuts.

“What’s a fils naturel?” inquired Liam. Clara looked over at me, eager for more knowledge.

On some matters, it is best to draw the veil.

“That’s a story for another time,” I replied firmly, and passed him the napkins so that he and his sister could start setting the table for dinner.

I hope you have enjoyed this slice of history and life at the Chateau as well.

A bientôt...and a very Merry and Happy fête de Noël to all!

P.S. Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com) will be happy to help you with your family vacation or holiday (2022 and onwards) gathering at the Chateau. They can help arrange and recommend expeditions and meals as well. Please feel free to call or write us.

We look forward to hearing from you!