A family expedition...school's out for La Toussaint...a visit to the medieval city of Laval...photo above shows the merry-go-round near the river Mayenne...

Dear friend,

“Il est petit, mais il fera l’affaire,” remarked Madame Francine, a gleam in her eye as she stood at the poulailler holding an empty casserole. “He’s small, but he’ll do the job.”

Her young rooster strutted around the fringes of the flock of hens.

Madame Francine's hens enjoy a varied diet. It's mushroom-hunting time in the countryside.

Ignoring their new paterfamilias, les poules were intent on pecking through wilted lettuce leaves for the leftovers from last night’s dinner. One had already bustled off in a corner to bolt down a greasy morsel of lardon before the others noticed. Three snatched at a cheese rind, tugging against each other with tightly clenched beaks. Perhaps wisely, the recent arrival refrained from attempting to join their mid-morning meal.

“Le pauvre Général,” sighed Madame Francine, “Quel dommage! What a waste!”

The General, named and admired for his formidable feathery chest, was the new coq’s predecessor. Two weeks ago, he had strayed outside at nightfall. If he were going to be eaten, she added, it’s a pity the fox got him. He would have made an excellent coq au vin for the Toussaint.

La Toussaint, All Saints Day, fell on Monday this year. This is the day to visit churchyards, to brighten grey stone graves with a few pots of purple and gold chrysanthemums. To light a candle before a statue of la Sainte Vierge and those patron saints who intercede for souls -- and perhaps roosters -- flying heavenward. This is a day to remember those who have gone before. Also, it is a day to celebrate life.

Families all through France unite, gathering around the table for a hearty feast. For though the damp leaves underfoot and dangling seed heads in the garden remind us that “all this earth droops toward death,” as an 11th-century warrior poet lamented, we are consoled by the joyful hubbub of brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, grandparents and grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins.

La Toussaint is also a school vacation, lasting two weeks. Encouraged by this week’s clear and sunny weather, we went on an expedition from Courtomer to Laval, the capital of the old duchy of Mayenne. A bit of culture would do the little ones good. And take their minds off the fate of Le Général.

La Mayenne is a pocket of territory surrounded by our département of the Orne in Normandy to the north, more of Normandy to the east, Brittany to the west, and Anjou and the Loire Valley to the south. Tucked between powerful and ambitious neighbors for much of history, the Mayenne developed its own formidable dynasty and a thriving textile industry to pay the bills. The dynasty persisted through the Renaissance, the early 1600s. Textiles flourished until the wild and persistent popularity of cotton, starting in the 1700s, upended a traditional fabrique based on locally-grown linen.

Cattle now graze the fields where blue-flowered flax once rippled in the breeze. La Mayenne is a quiet place, with a soft landscape that drains into the broad river running through its center. Its capital city is Laval, founded around 1020.

We think of a city as a naturally occurring phenomenon, arising from ancient settlements where men have lived and traded since hunting and gathering gave way to agriculture in the mists of time. But Laval was a conscious creation. It owes its existence to a "via romana" that was already about 1,000 years old when the first stones of the new settlement were laid. The Romans used this road as a major thoroughfare between the Atlantic Coast and the Loire Valley.

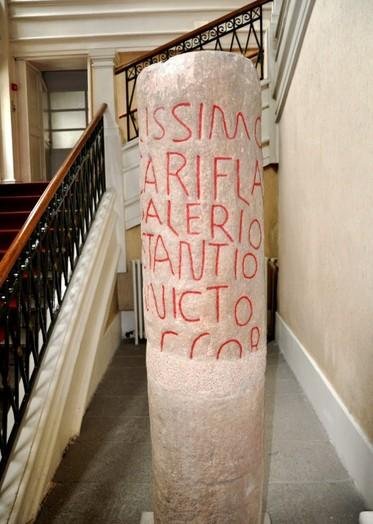

A Roman milepost from the ancient "via romana" that runs through Laval, now in stairwell of the Mairie of Laval.

Throughout their Empire, which included France, the Romans had built straight, solid roads to facilitate the movement of troops and tribute, people and goods. Invading Barbarians from the North used them in turn to drive out Rome’s imperial servants and armies. Now, in the turbulent 10th and 11th centuries, the road from the coast eased the way for marauders and rivals to move from Normandy and Brittany into the rich lands of the counts of Maine and southward to the sunny, fertile Loire Valley. But on a rocky embankment of the Mayenne, the old Roman road came to a halt. A ford took travelers from the river’s edge to the other side.

The count of Maine at the time was Herbert Eveille-Chien, whose surnom “Wake the Dog” suggests rightly that he was constantly on the lookout for danger. Urged by his domineering master to the south, Foulque Nerra, count of Anjou, he was determined to defend the crossing. Herbert appointed a loyal neighbor to be baron of the valley. Now known as Guy 1er de Laval, the new seigneur promptly built a vast “chasteau” on the promontory overlooking the ford.

Guy VII de Laval, painted by the great French Renaissance portraitist, François Clouet.

For the next six centuries, Guy’s descendants steadily built a base of wealth and power in Laval. Protected by the Chateau de Laval, the old Roman road could be used for commerce. Houses sprang up, built onto the Chateau’s strong walls. Plentiful water and forests in the surrounding valley of the Mayenne encouraged ironworks, forges, and textiles. And careful marriages and prudent alliances united the house of Laval with the counts of Maine and Anjou, the scattered kingdoms of Brittany, the dukes of Normandy, and the royal house of France.

Immersed in these reflections as we strolled through the gates of the Chateau, we were brusquely interrupted. La petite Dorothée stood staring up at the bronze statue of a lady in medieval dress. “Who is she?” she wanted to know.

Placed on the grounds of the Vieux Chateau de Laval in 1922, this was a monument to Béatrix de Gavre, married in 1289 to Guy IX le Borgne, the One-Eyed. Béatrix brought Laval not only a stupendous dowry, represented by the bulging purse dangling from her girdle, but Flemish weavers. In her left hand she holds a “navette,” a shuttle. The knowledge and skill of Béatrix’ weavers combined with an abundant supply of flax was the primary source of prosperity in the Mayenne for the next 500 years.

The bronze of Béatrix de Gavre in the gardens of the Vieux Chateau, against a backdrop of "vigne vièrge."

“All the countryside are spinners and weavers,” wrote a government official in 1803. “When they can’t farm, during the bad seasons, they take up the shuttle…often they are both grower, maker and dealer…everyone, in the towns, too, trades, sells, and makes cloth and thread.”

Of course, this dependance on one industry was not what economists call “anti-fragile.”

A report on the political situation in the Mayenne during the French Revolution warned, “This département’s almost unique resource is the fabrication of cloth and spinning; it is the only way that a large population can subsist on this sterile land.”

Public statues probably reflect nostalgia, our profound human protest against drooping unto decline. The statue had been commissioned by the Société des Arts réunis de Laval. These wealthy and enthusiastic amateurs of art and culture turned to a well-known contemporary, the Parisian sculptor Paul Loiseau-Rousseau. Loiseau-Rousseau had recently won a second-place medal at the 1905 Salon de Paris, the same year and exhibition which introduced the work of “les Fauves” – Matisse and company -- and Henri Rousseau. Le Douanier Rousseau was a native of Laval; three of his “naïve” works are to be found in the adjacent museum in the Vieux Chateau.

By the time Béatrix de Gavre appeared on the grounds of the Chateau in her bronze form, in 1922, the textile industry in Laval was already doomed. The destruction of capital and of old ways of earning money that occurred during the French Revolution – with its years of inflation and warfare, its new laws, new rules and its new rich, its ideals of free trade, its fascination with machinery and novel methods – dealt a blow to a world anchored in a tight, ancient cycle of field to loom to marketplace. The developments of the next two hundred years – global trade, industrialization, workplace change -- finished it off.

Dorothée skipped on ahead, humming cheerily.

The day was waning. Young James was starting to look pale. We left the grounds of the Chateau and ventured into the streets. La Grande Rue is the old Roman road. In days of yore, it was “une porte principale de la Bretagne,” a main “door” to Brittany and the coast. Pilgrims used it to reach le Mont Saint-Michel, now only an hour and a half by car from the city.

The children looked longingly into the window of a pâtisserie. France has taken up Hallowe’en with enthusiasm. On this charming cobblestoned street, lined with medieval houses in colombage, the pâtissier displayed grinning pumpkins in sugar and egg whites mingled with the more traditional autumn motifs of candy mushrooms and fallen leaves.

“Goûter!” piped up Dorothée. A goûter, although literally a tasting, is a hearty afternoon meal of brioche and jam, pain au chocolat, petits gâteaux and hot milk.

Le petit Charles, who barely speaks, gurgled.

“He wants chocolat chaud!” urged his sister.

“Alright,” I said. “But be sure to say “Bonjour Messieurs, Mesdames” if anyone else is in the shop.”

Dorothée looked pugnacious. At three and a half, she contests all conventional behavior.

“And say “S’il vous plaît, Madame la boulangère” and “Merci, Madame”” hissed James, who at six has a lively dread of the faux pas. He glared at his little sister and brother for good measure.

Dorothée frowned. Charlot gave his usual good-natured smile and held up his arms to be carried.

The lights were on in the shop, inviting us to come in from the chilly November afternoon. Inhaling the fragrant scent of buttery brioche, we pushed open the door.

Next week, more about our expedition…and the house of Laval’s connection – especially of the rebellious Guyonne de Laval -- to the family at Chateau de Courtomer.